Author

Author

|

Topic: We're Fucked - The Coming Economic Crisis (Read 164946 times) |

|

Fritz

Adept

Gender:

Posts: 1746

Reputation: 7.61

Rate Fritz

|

|

Re:We're Fucked - The Coming Economic Crisis

« Reply #180 on: 2014-06-02 12:23:12 » |

|

Just a state of the Union for this thread

Cheers

Fritz

What you need to know about the economy in 2014

Source: The Guardian

Author: Heidi Moore

Date: 2014.06.02

Jobless baby boomers, falling wages and rose-coloured glasses: what policymakers are trying to understand

Ben Bernanke, despite his sage's beard, isn't sure what to tell you about the economy. Photograph: Dominick Reuter/Reuters

Any week in which the economy takes center stage tends to be a headache to even the most committed reader of news. What happens in DC often stays in DC – if only because many of the economic decisions made there seem so remote and alienated from the rest of the country. But the decisions made in Washington play a huge part of our daily lives. The Federal Reserve's giant stimulus program, in the spotlight today, is one example. The president's proposals in the state of the union were another. These two events, taken together, would tell us we have an improving economy.

It would be a hard sell.

Disagreement about the economy

Here's the problem: Even the experts don't agree on where the economy has gone. Some believe it's improving. Some believe the evidence is thin. Ian Sheperdson, the founder of Pantheon Macroeconomics, noted a more optimistic tone in the Fed's description of the economy after its monthly meeting this week:

The statement is a bit more upbeat than in December, suggesting the Fed is (even) more comfortable with its decision to taper. Growth is now said to have "picked up in recent quarters", compared to "expanding at a moderate pace" in December, while consumption and investment "advanced more quickly in recent months", compared to merely "advanced" in December. And fiscal restraint "is diminishing", compared to "may be diminishing".

For the Fed, a small adjustment like "advanced more quickly" is as celebratory as putting a lampshade on your head at a party. It's meaningful because it allows the central bank to reduce the $65 billion of stimulus it's pouring into the bond market every month. Tapering the stimulus indicates that the Fed believes the economy, and stock markets, are strong enough to stand on their own without the central bank's help.

It's a simple equation: a better economy means less stimulus.

There's unity in that optimism this week. President Obama's state of the union has expressed it too, as the president spoke last night about job growth and a housing rebound even as he focused on inequality and growing poverty.

Wall Street investors and economists weren't surprised by the Federal Reserve's decision to keep reducing its largest and longest stimulus program – although their views diverge on whether the economy is still improving.

President Obama omitted figures about workers dropping out of the labour force from his 2014 state of the union. Photograph: Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images

The Fed and the experts aren't always right

But here's something everyone forgets: the Fed is often wrong.

Guy LeBas, of Janney Capital Markets, made that point after the Fed's meeting: he said that the Fed's optimism was at odds with the unimpressive economic statistics in January, particularly the jobs numbers. Bad weather hurt several economic measures in late December. LeBas reminded us that the Federal Reserve has a history of overly optimistic pronouncements – only to regret its boisterous proclamations later.

Here's LeBas: "There have been at least three other occasions (spring 2010, spring 2011, and summer 2012) in which economic optimism and forecasts have grown hopeful, only for reality to quash them with a string of disappointing data readings. To borrow from the late Pete Seeger, 'Education is when you read the fine print. Experience is what you get if you don’t.' At this point in the post-global financial crisis cycle, we should all have plenty of experience with economic expectations, yet it seems leaders are focused only on the fine print."

LeBas makes a good point. The happy talk often misleads. Currently, there are some serious problems with the economy that people don't talk about enough, or don't talk about in the right way. For instance, it's common for politicians, including the president, to crow about the falling unemployment rate. They rarely mention that it's falling because people are dropping out of the workforce.

The jobs picture

Before its happy-talk January decision, the Federal Reserve held a more contentious court in December. At its December meeting, board members of the Federal Reserve nearly came to blows over the employment crisis. (Actually an "exchange of views" took place, but at the mild-mannered Fed, that phrase has plenty of verbally violent connotations.)

The truth is that even the experts can't agree what to do about America's unemployment crisis, or why we're even having one.

Some members of the Fed believed that fewer Americans are employed mainly because older workers are retiring.

There may be some truth to that. Here's the thing: if it is true, it goes deeper. It's not just older workers leaving the workforce; it's older women, specifically, women between 45 and 54-years-old. Their employment rate has fallen by about 2% this year, more than any other age group and more than twice the rate of women between the ages of 35-44, according to research from Ian Shepherdson, of Pantheon Macroeconomics.

Other members of the Fed argued with a litany of reasons why the economy is still full of warning signs. Some pointed to the employment rate of 62.8%, the lowest since Jimmy Carter was telling Americans to wear sweaters rather than pay for heat. Others talked about the high numbers of people who have been employed for six months or more, currently tallied at 3.9 million people. Still others looked to the stagnant number of people working part-time because they can't find full-time work. And finally, some argued the importance of the low employment rate for workers between the ages of 25 and 54, as seen in this alarming chart.

A Goldman Sachs economist has said companies are becoming more profitable by paying workers less. Photograph: Brendan Mcdermid/Reuters

The stimulus and you

Those are the kinds of statistics that led the Fed to start the stimulus, or QE.

Quantitative easing is not difficult to understand. The Fed buys bonds from banks and investors: mortgage securities, Treasury bonds, all to the tune of $65bn a month. Initially, it had big ambitions: "to put downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, help ease financial conditions, and promote a stronger recovery".

Snorfling up all those bonds fattened the Fed's balance sheet to $4tn. Even worse, the Fed arguably lost its waistline for nothing. The Fed's bond-buying has shown lackluster results lately. After four years, QE hasn't created jobs. It has lowered interest rates to the point where it hurt people who like to save money; with interest rates near zero, your money is earning roughly the same interest by sitting under your mattress as it is in your savings account.

The primary benefit of QE was to your 401k. By buying bonds, the Fed pushed down the returns on bonds and scared investors out of buying as many as they would like. Yet those investors have to buy something. As a result, they bought other assets: stocks, and the bonds of countries like Turkey and South Africa. The record highs in the S&P 500 last year? You can thank the Fed for that.

2014 and inequality's future

There's a good chance that these trends in inequality will continue this year. There's one plan that Obama has for the US, another corporations have for the US, and they are not aligned.

The main problem is that corporations like making money and don't like paying it to people other than shareholders. Corporate profit margins are the highest they've been since 1968, according to Goldman Sachs. A prominent economist there says companies are becoming profitable by paying workers less. That has led to rich corporate profits and a lot of low-wage, temporary jobs flooding the labor market. What about the manufacturing insourcing craze? In fact, says Goldman Sachs, even when US companies bring jobs to the US from overseas, they only do it when they can pay those people less. Yes, those jobs still pay more than flipping burgers – but they will not pay as well as other manufacturing jobs.

One reason why companies are paying workers less: the percentage of Americans in labor unions has fallen to 11%, the lowest since the second world war. Union workers made $943 a week in 2013, compared to only $742 for those not in a union.

Everything else, however, is mostly conjecture.

The saddest part of the December Fed discussion was this: "a couple of participants had heard reports of labor shortages, particularly for workers with specialized skills."

That tells you a lot. Yes, our monetary policy is based on rumors sometimes -- economists who know a guy who knows a guy. It's a good reason to take everything you hear about the economy from Washington with a grain of salt.

|

Where there is the necessary technical skill to move mountains, there is no need for the faith that moves mountains -anon-

|

|

|

David Lucifer

Archon

Posts: 2642

Reputation: 8.38

Rate David Lucifer

Enlighten me.

|

|

Re:We're Fucked - The Coming Economic Crisis

« Reply #181 on: 2014-06-03 09:22:37 » |

|

source: Barrons

Piketty: A Wealth of Misconceptions

Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty's thoughtful manifesto, sadly gets capitalism all wrong.

May 31, 2014 12:39 a.m. ET

Reviewed by Donald J. Boudreaux

Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century might soon stand with Karl Marx's Capital, which inspired its title, as one of the most influential economic masterworks of the past 150 years. But sad to say, this 696-page tome, ably translated by Arthur Goldhammer, is no more enlightening about capitalism in the 21st century than Marx's Capital was about capitalism in the 19th century.

As a publishing phenomenon alone, the Paris School of Economics professor's treatise, which has been hailed by three Nobel laureates—Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, and Robert Solow—commands our attention. It is also noteworthy as a symptom of a perverse ideology that seems to dominate progressive thinking, including that of President Barack Obama and President François Hollande of France, and of a flawed method of economic analysis.

Many of us care about whether, and to what extent, the broad masses of people have improved absolutely their material conditions of life. While Piketty (pronounced "PEEK-et-tee") doesn't entirely ignore that question, he focuses instead on the causes and cures of relative disparities in monetary income and wealth across groups of people and over centuries. Some ways of narrowing those disparities, such as punitive rates of taxation, might run the risk of dragging down everyone, rich and poor alike. But for Piketty, the importance of diminishing monetary inequalities is so monumental that he all but totally ignores such risks.

Piketty's method of doing economics involves frequent grand proclamations about "social justice" and economic "evolutions," but he offers no analyses of the dynamics of individual decision-making, often referred to as "microeconomics," that should be central to the issues he raises.

The author hovers instead in the economy's stratosphere, gazing down on the only phenomena visible from such a distant perch—big statistics such as population growth or the share of national income "claimed" by the very rich. Revealingly, Piketty writes of income and wealth as being claimed or "distributed," never as being earned or produced. The resulting statistics are too aggregated—too big-picture—to reveal what is happening to individuals on the ground.

Instead of actually looking at the behavior behind his statistics, the author serves up ad hoc and ultimately unpersuasive theories about the "behavior" of his big statistics themselves, including such hulking impersonal aggregates as the return to capital and the ratio of national wealth to national income. He imagines that such aggregates interact in robotic fashion through a logic of their own, unmoved by individual human initiative, creativity, or choice.

CONSIDER PIKETTY'S CENTRAL theory, that the rate of return on capital, which he labels "r," tends to be greater than the rate of economic growth, or "g." For the author, the fact that r runs faster than g—by several percentage points, by his reckoning—alone seals capitalism's fate, because it implies that owners of capital must get increasingly richer than nonowners. Because capital ownership is itself unevenly "distributed" across society, wealth and income disparities must in turn worsen, "impoverishing" the middle classes and the poor alike, while giving a relatively small number of rich elites both vast resources and disproportionate influence over government policy-making.

Despite the logical implications of return on capital being greater than economic growth, Piketty doesn't think that the plutocraticization of society is inevitable. First of all, it can be arrested and even reversed by calamities such as world wars or Soviet-style communism, the destructive effects of which fall disproportionately upon the rich. Alas, he opines that the welcome consequences of such correctives are only temporary.

But another, more lasting remedy is readily at hand: hard-hitting taxation. Piketty calls for greater and more progressive taxation, not only of incomes—at a top bracket of at least 80%—but also of wealth, preferably to be enacted globally, lest differential tax burdens prompt plutocrats to flee from high-tax to low-tax jurisdictions. While he isn't optimistic about the likelihood of the necessary government cooperation, he's willing to settle for whatever steps more-enlightened governments might take to soak the rich—and especially such steps as might be accompanied by greater cross-border sharing of information about bank accounts and other investments owned by foreigners.

Flaws aplenty mar Piketty's telling of the capitalist saga, flaws that spring mainly from his disregard for basic economic principles. None looms larger than his mistaken notion of wealth.

Every semester, I ask my freshman students how wealthy they would be if they each were worth financially as much as Bill Gates but were stranded with all those stocks, bonds, property titles, and bundles of cash alone on a desert island. They immediately see that what matters is not the amount of money they have but, rather, what that money can buy. No principle of economics is more essential than the realization that, ultimately, wealth isn't money or financial assets but, rather, ready access to real goods and services.

Piketty seems barely aware of this reality, focusing on differences in people's monetary portfolios. He therefore ignores the all-important supply side: what people—rich, middle class, and poor—can buy with their money. Yet, to the extent that inequalities are at all relevant, the only ones that really matter are inequalities in access to real goods and services for consumption. Bill Gates' living quarters are larger and more elegant than mine and, I dare say, yours. But even the poorest people in market economies have seen their ability to consume skyrocket over time. And the poorer they once were, the greater has been the enhancement of their ability to consume.

If we follow the advice of Adam Smith and examine people's ability to consume, we discover that nearly everyone in market economies is growing richer. We also discover that the real economic differences separating the rich from the middle class and the poor are shrinking. Reckoned in standards of living—in ability to consume—capitalism is creating an ever-more-egalitarian society.

THE U.S. IS THE bête noir of Piketty and other progressives obsessed with monetary inequality. But middle-class Americans take for granted their air-conditioned homes, cars, and workplaces—along with their smartphones, safe air travel, and pills for ailments ranging from hypertension to erectile dysfunction. At the end of World War II, when monetary income and wealth inequalities were narrower than they've been at any time in the past century, these goods and services were either available to no one or affordable only by the very rich. So regardless of how many more dollars today's plutocrats have accumulated and stashed into their portfolios, the elite's accumulation of riches has not prevented the living standards of ordinary people from rising spectacularly.

Furthermore, these improvements in real living standards have been undeniably greater for ordinary folks than for rich ones. In 1950, Howard Hughes and Frank Sinatra could easily afford to pay for the likes of overnight package delivery, hour-long transcontinental telephone calls, and air-conditioned homes. For ordinary Americans, however, these things were out of reach. Yet, while today's tycoons and celebrities still have access to such amenities, so, too, do middle-class and even poor Americans. This shrinking gap between the real economic fortunes of the rich and the rest of us should calm concerns about the political dangers of the expanding inequality of monetary fortunes.

Flaws in the author's stratospheric viewpoint are also on display when we try to think in human terms about the inevitability of the return on capital, at 4% to 5%, exceeding the growth rate of economy, at 1% to 1.5%. According to the author, that gap of a few percentage points, when compounded over many years, can render economic inequality "potentially terrifying." But two key factors make it quite difficult for that tendency to persist for very long in the lives of most individuals.

To begin with, advance and retreat, rather than permanence, tends to characterize the pattern of most successful businesses. Sooner or later, the entry of competitors and of changing consumer tastes curbs their growth, when not reducing their size absolutely or even bankrupting them. In 2013 alone, 33,000 businesses in the U.S. filed for bankruptcy, a typical figure for a year of economic expansion. Second, and more importantly, successful capitalists rarely spawn children and grandchildren who match their elders' success; there is regression toward the mean. Note that the terrifyingly successful capitalist Bill Gates will likely not be succeeded by younger Gateses prepared to capitalize on his success.

Even leave aside plans like those of Gates and Warren Buffett to give away much of their fortunes, or the redistributive role of philanthropy generally. The empirical data suggest that turnover is the norm among wealthy capitalists, rather than the building of a permanent plutocracy. The IRS' list of "Top 400 Individual Tax Returns" provides evidence of instability at the top. Over the 18 years from 1992 through 2009, 73% of the individuals who appeared on that list did so for only one year. Only a handful of individuals made the list in 10 or more years. Wealth gets diluted over time when left to multiple heirs, and is further diluted by estate taxes, philanthropy, and changes in market conditions.

PIKETTY'S PRONOUNCEMENTS about the stability of capitalist wealth deny such realities. He writes, for example, that "Capital is never quiet: it is always risk-oriented and entrepreneurial, at least at its inception, yet it always tends to transform itself into rents as it accumulates in large enough amounts—that is its vocation, its logical destination." Read: The risky, entrepreneurial element in business formation eventually recedes in importance until the business naturally evolves toward its "logical destination"—that of a perpetual cash machine that regularly spits out "rents."

In a similar vein, Piketty observes, "[W]hat could be more natural to ask of a capital asset than that it produce a reliable and steady income: that is in fact the goal of a 'perfect' capital market as economists define it." It may be "natural" to ask this of a capital asset. But only economists who talk of "perfect" capital markets are naive enough to expect a "yes" answer.

If Piketty really believes in a "perfect" capital market yielding capitalists reliable and steady income, he might wonder why the bankrupt book-selling giant Borders is no longer around to sell his books, while Amazon.com has grown up to challenge all manner of bricks-and-mortar retailers. In his world, capitalism is a system of profits; in the real world, it's a system of profit and loss.

Piketty's disregard for basic economic reasoning blinds him to the all-important market forces at work on the ground—market forces that, if left unencumbered by government, produce growing prosperity for all. Yet, he would happily encumber these forces with confiscatory taxes.

Commendably, though, he expresses concern about the potential for his tax regime to expand the size of government: "[B]efore we can learn to efficiently organize public financing equivalent to two-thirds to three-quarters of national income," he cautions, "it would be good to improve the organization and operation of the existing public sector." It would indeed be "good" to make such improvements. I'd like to imagine that, if Karl Marx were alive today, he'd sadly inform his less-experienced colleague that, 150 years ago, socialists had that very same idea. It did not work out as hoped.

|

|

|

|

|

Fritz

Adept

Gender:

Posts: 1746

Reputation: 7.61

Rate Fritz

|

|

Re:We're Fucked - The Coming Economic Crisis

« Reply #182 on: 2014-06-04 14:50:32 » |

|

Seems though that the gangsterism and banksters behaviour play a big part (e.g. the 2007 bust) no one is discussing this.

Cheers

Fritz

Source: Arnold Kling's Blog

Author: Arnold Kling

Date: 2014.05.23

Robert Solow on Piketty

Solow writes,

if the economy is growing at g percent per year, and if it saves s percent of its national income each year, the self-reproducing capital-income ratio is s / g (10 / 2 in the example). Piketty suggests that global growth of output will slow in the coming century from 3 percent to 1.5 percent annually. (This is the sum of the growth rates of population and productivity, both of which he expects to diminish.) He puts the world saving / investment rate at about 10 percent. So he expects the capital-income ratio to climb eventually to something near 7 (or 10 / 1.5). This is a big deal, as will emerge. He is quite aware that the underlying assumptions could turn out to be wrong; no one can see a century ahead. But it could plausibly go this way.

…The labor share of national income is arithmetically the same thing as the real wage divided by the productivity of labor. Would you rather live in a society in which the real wage was rising rapidly but the labor share was falling (because productivity was increasing even faster), or one in which the real wage was stagnating, along with productivity, so the labor share was unchanging? The first is surely better on narrowly economic grounds: you eat your wage, not your share of national income. But there could be political and social advantages to the second option. If a small class of owners of wealth—and it is small—comes to collect a growing share of the national income, it is likely to dominate the society in other ways as well. This dichotomy need not arise, but it is good to be clear.

Both Tyler Cowen and Solow make the same point about wages, but they do so subtly. Let me be blunt: Piketty’s nightmare scenario, in which capital accumulates and has a high return, is a terrific scenario for wages in absolute terms. If workers care about what they can consume, as opposed to the ratio of their net worth to that of the capital owners, they would hate to see any policy that might interfere with the high rates of investment that Piketty is envisioning. Note, however, that I personally would not concede that the distinction between workers and capital-owners is as clear-cut as it is in the Solow growth model.

The tone of Solow’s review is generally laudatory. It also is by far the clearest explanation of Piketty’s argument that I have read. It reflects Solow’s command of the logic of economic growth as well as his abilities as a teacher.

I think that Solow arrives at a higher evaluation of the book than I would for two reasons. First, Solow gives Piketty the benefit of the doubt on nearly every uncertain issue. For example, on the crucial assumption that Piketty makes that the rate of return on capital remains steady even as the capital-income ratio creeps ever higher, Solow writes,

Maybe a little skepticism is in order. For instance, the historically fairly stable long-run rate of return has been the balanced outcome of a tension between diminishing returns and technological progress; perhaps a slower rate of growth in the future will pull the rate of return down drastically. Perhaps. But suppose that Piketty is on the whole right.

On another issue, the fact that inequality is high between different workers, not just between workers and capitalists, Solow offers a hand-waving defense of Piketty. Solow writes,

Another possibility, tempting but still rather vague, is that top management compensation, at least some of it, does not really belong in the category of labor income, but represents instead a sort of adjunct to capital, and should be treated in part as a way of sharing in income from capital…

it is pretty clear that the class of supermanagers belongs socially and politically with the rentiers, not with the larger body of salaried and independent professionals and middle managers

To this, I would say: why draw the line at supermanagers? Why not say that the salaries of college professors that are paid out of university endowments are “a way of sharing income from capital”? The way I look at it, the amount of income that does not represent “a sort of adjunct to capital” (including human capital) is miniscule, perhaps less than 1 percent of GDP.

My second disagreement with Solow is that he, like Piketty, omits any discussion of risk as a component of “r.” In that regard, Tyler Cowen’s skeptical review better accords with my own thinking.

The way I see it, Piketty and Solow work with models that incorporate homogeneous workers (with no differences in human capital) and homogeneous capital (with no differences in ex ante risk or ex post returns). The real world is so far removed from those models that I simply cannot buy into the undertaking.

|

Where there is the necessary technical skill to move mountains, there is no need for the faith that moves mountains -anon-

|

|

|

Fritz

Adept

Gender:

Posts: 1746

Reputation: 7.61

Rate Fritz

|

|

Re:We're Fucked - The Coming Economic Crisis

« Reply #183 on: 2014-06-06 15:50:59 » |

|

Seems while we piss in each others corn flakes in Europe, the West's financial future is slipping away

Cheers

Fritz

The Great Western Gas Fiasco

Source: Information Clearing House

Author: Eric Margolis

Date: 2014.05.24

By Eric Margolis

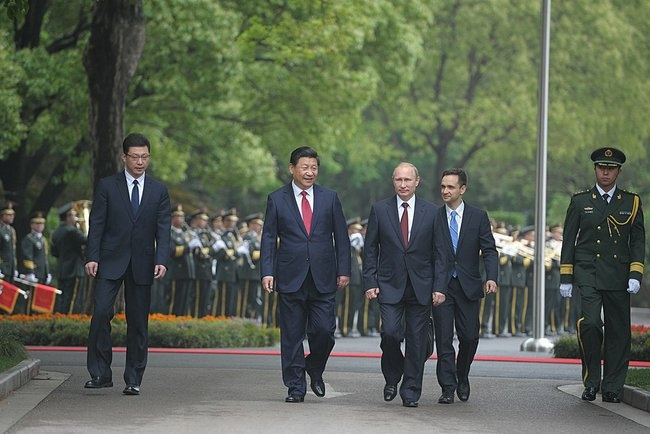

May 24 2014 "ICH" - GENEVA – Russia’s leader Vladimir Putin usually wears a perfect poker face. But last week in Shangahi, the icy-cold Russian president came awfully close to bursting into a big grin.

And why not? Putin had just stolen a march on his western rivals. The US-British attempt to wound Russia’s economy and punish Putin for disobedience had just blown up in their red faces.

After 20 years of difficult talks, Russia and China had just signed a huge deal that called for Russia to export 38 billion cubic meters of gas worth some $400 billion to China. The agreement begins in 2018 and will involve one of the globe’s largest engineering projects that links Russia’s remote gas fields to China’s pipeline system.

In addition, China will invest at least $20 billion in Russian industry and boost imports of Russian products, notably military systems. China will become Russia’s largest trade partner.

This was not the much ballyhooed “pivot to Asia” that President Barack Obama expected. It is, however, the long-dreaded embrace between the Chinese dragon and Russian bear that has given western strategists the willies.

One must suspect that the recent fracas in Ukraine was the last straw that pushed China to make a strategic alignment with Russia. Until now, the two great powers had quietly cooperated, not always without problems. Thanks to all the bluster and sabre-rattling from the US and its allies over Eastern Europe and the South China Sea, China decided to deepen and expand its entente with Moscow.

The Republicans in the US Congress who have been beating the war drums and calling for Obama to get tough with Russia (whatever that means) now share blame for pushing Moscow into China’s arms. All perfectly predictable and perfectly dumb. A diplomatic fiasco of the first water.

Russia has thus given its economy a big boost and made western sanctions look inconsequential. Chinese funds will allow cash-strapped Russia to modernize its oil and gas industry. The new gas pipelines will be a major economic boost for Russia’s distressed eastern regions and Siberia.

If the gas deal works and prospers, it will serve as a template for heightened Sino-Russian cooperation in military projects, such as fifth generation fighter aircraft, missile systems, naval forces and advanced electronics. Until today, Russia had been reluctant to share more advanced military systems with China because of China’s copying of Russian technology, then refusing to pay adequate royalties.

For China, the deal offers many advantages. China has been energy deficient for years. Beijing desperately needs to find new energy sources to fuel its growing economy. Russian gas offers a clean alternative to the filthy coal China has used for power and heat. Estimates are that a switch to gas will reduce air pollution by at least 25% in China’s northern cities, maybe much more. Having gasped for air through numerous Beijing nights, I fully appreciate what this means.

Russia has long been reluctant to cooperate too closely with China on Far East industrial projects. Russians have little love for China – or “Kitai” – because China evokes memories of the Mongol-Tatar invasions that ravaged large parts of Russia for hundreds of years. Distrust and even straight out dislike is wired into the mentality of many Russians. During the 19th century, Russia joined the western powers and Japan in raping China.

Demography lies at the heart of Russia’s fears of China. Russia’s far eastern regions, with the vital port of Vladivostok, has only 7.4 million citizens. Ten times as many Chinese lived just across the border in the northeast region known as the “Dongbei.” This highly strategic region and Manchuria became an arena of conflict at the end of the 19th century between Russia, Japan, and China, leading to the bloody 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War, the first big, modern war of the 20th century.

Some 1.5 million Chinese infiltrate annually over the Russian border and settle illegally, producing a situation akin to that between the US and Mexico. Fears are expressed in Moscow that the 2 million illegal Chinese settlers in Russia’s Far East may one day expand to 20 or 30 million, outnumbering Russian inhabitants.

When I was invited in 1980 by Chinese military intelligence to “exchange views” in Beijing, I cheekily asked how long it would take for the Chinese Army to take Vladivostok. After a long, uncomfortable silence, a general spat out, “one week.”

Russia still holds vast tracts of land seized in the mid 1800’s from China. Beijing and Moscow will have their work cut out to resolve lingering disputes and build mutual respect and trust. There is a big deficit on both sides right now.

Today, China’s growing energy imports are very vulnerable to interdiction. The US and lately India have the capability to block inbound Chinese oil tankers and maritime cargo exports, either of which would shut down China’s major industries.

Key choke points would be the inner and outer island chains of the South and North China Seas, and the narrow Malacca Strait. India’s new aircraft carriers and submarines are being specifically built to interdict China’s oil imports.

Pipeline oil from Russia would be secure from most attacks and offer China its long-sought energy security.

This new deal is so good on many levels that old fears and mistrust must yield to its logic.

Most important, the Sino-Russian energy deal may further alter the world’s balance of power to the East. Russia and China working in tandem could offset the great power and wealth of the US and its rich allies. It is a major geopolitical event.

Eric S. Margolis is an award-winning, internationally syndicated columnist. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, the International Herald Tribune the Los Angeles Times, Times of London, the Gulf Times, the Khaleej Times, Nation – Pakistan, Hurriyet, – Turkey, Sun Times Malaysia and other news sites in Asia. http://ericmargolis.com

Copyright Eric S. Margolis 2014

|

Where there is the necessary technical skill to move mountains, there is no need for the faith that moves mountains -anon-

|

|

|

|

|

Fritz

Adept

Gender:

Posts: 1746

Reputation: 7.61

Rate Fritz

|

|

Re:We're Fucked - The Coming Economic Crisis

« Reply #185 on: 2014-06-10 16:39:54 » |

|

Buy it's own rules though; nothing we've done.

Cheers

Fritz

Source: Bloomberg

Author: Sandrine Rastello

Date: 2014.06.06

.jpg )

Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, speaks during a news conference at the U.K. Treasury in London on June 6, 2014.

The International Monetary Fund’s headquarters may one day shift to Beijing from Washington, aligning with China’s growing influence in the world economy, the fund’s managing director said.

Christine Lagarde, speaking late today in London, said IMF rules require the main office be located in the country that is the biggest shareholder, which the U.S. has been since the fund was formed 70 years ago.

The IMF founding members “decided that the institution would be headquartered in the country which had the biggest share of the quota, which chipped in the biggest amount and contributed most. And that is still today the United States,” she said in response to questions at the London School of Economics.

“But the way things are going, I wouldn’t be surprised if one of these days the IMF was headquartered in Beijing for instance,” she said. “It would be the articles of the IMF that would dictate it.”

Lagarde said the IMF has a good relationship with China, the world’s second largest economy and she praised the government’s commitment to fighting corruption.

She had less kind things to say about the U.S., which remains the “outlier” among Group of 20 countries to approve an overhaul of the ownership of the 188-member organization. The plan would give emerging markets more influence and would elevate China to the third-largest member nation.

Lagarde said there is “frustration by countries like China, like Brazil, like India, with the lack of progress in reforming the IMF by adopting the quota reform that would give emerging-market economies a bigger voice, a bigger vote, a bigger share in the institution and I share that frustration immensely.”

“The credibility of the institution, its relevance in the world in conducting the mission that it was assigned 70 years ago is highly correlated with its good representation of the membership,” she said. “We cannot have a good representation of the membership when China has a teeny tiny share of quota, share of voice when it has grown to where it has grown.”

|

Where there is the necessary technical skill to move mountains, there is no need for the faith that moves mountains -anon-

|

|

|

|