Author

Author

|

Topic: The Flipping Point (Read 98898 times) |

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4289

Reputation: 8.16

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:The Flipping Point

« Reply #210 on: 2009-03-20 06:18:25 » |

|

[Iolo Morganwg] Solar variation in irradiance is not the only factor influencing the climate, something warmers fail to accept (or understand). Solar variations in its magnetic field output are more important than the simple heat received. Warmers go wild when one talks to them about close correlation between solar system influences (as baricecenter, Jovian cycles, etc, something that Dr. Timo Niroma has explored quite well). Of course, warmers get near the cardiac arrest when hearing about works by Abdusamatov, Charavátova, and other astronomers and astrophysicists.

[Hermit] I haven't noticed any unusual cardiac activity. Then again I do tend to discount theories from people, be they never so clever, that appear to run counter to the consensus and require me to discount well understood physics. For example, when I am told that greenhouse gases rather than acting as a greenhouse are somehow acting as thermal transfer systems on a planetary scale, contradicting known physics by absorbing radiant heat, then somehow rising through the atmosphere and again contravening physics by conducting the heat previously absorbed back into space, which seems congruent with how he is reported, then to quote Blunderov, my tail goes all bushy and my BS detector goes into the red. Why we are not drowning in cold gases is not addressed in anything found. Neither is there an explanation for why we don't have lunar style unmoderated day night thermal perturbations. No explanation for why the atmosphere seems to get colder the further from the Earth we venture either. Not even a mention of Brownian motion and molecular energy transfers or which brand of greenhouse gas ignores the physics I grew up with, even though that would probably earn the discoverer a Nobel prize. Instead of just throwing out obscure hints about weird personalities making strange claims (check Google Citations to see why I conclude this) perhaps Iolo will provide some actual claims, predictions and supporting hypothesis for us to gnaw on?

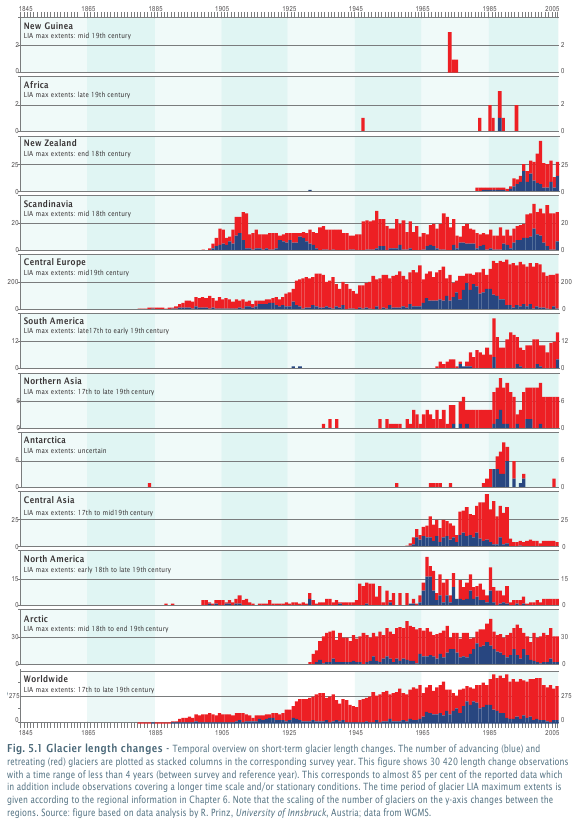

[Iolo Morganwg] So, as stated in my previous post, many glaciers are advancing and many more are retreating. But more are stable and the overwhelming majority are uncertain. See the graph from WGMS (World Glacier Monitoring Survey) data:

[Hermit] WGMS tends to report on glaciation/deglaciation in mass units converted to m of water equivalent. Far from the "business as usual", inconclusive picture you appear to be attempting to advocate, WGMS claims that annual mass loss continues to be highly significant The data you present appears anomalous. Perhaps you could cite a WGMS source for them.

In their Sept 2008 report on glacier changes, in Chapter 7 they report:Looking at individual fluctuation series, a high variability and sometimes contradictory behaviour of neighbouring ice bodies are found which can be explained by the different glacier characteristics. The early mass balance measurements indicate strong ice losses as early as the 1940s and 1950s, followed by a moderate ice loss between 1966 and 1985, and accelerating ice losses until present. The global average annual mass loss of more than half a metre water equivalent during the decade of 1996 to 2005 represents twice the ice loss of the previous decade (1986–95) and over four times the rate of the decade from 1976 to 1985. Prominent periods of regional mass gains are found in the Alps in the late 1970s and early 1980s and in coastal Scandinavia and New Zealand in the 1990s. Under current IPCC climate scenarios, the ongoing trend of worldwide and rapid, if not accelerating, glacier shrinkage on the century time scale is most likely to be of a non-periodic nature, and may lead to the deglaciation of large parts of many mountain ranges by the end of the 21st century. While in my opinion the attached graph from Chapter 5 speaks for itself. The text and data in that report also appears to disagree with your bullet points:

The global averages (i, ii, iii) reveal strong ice losses in the first decade after the start of the measurements in 1946, slowing down in the second decade (1956–65), followed by a moderate mass loss between 1966 and 1985, and a subsequent acceleration of ice loss until present (Fig. 5.8 a—f). The mean of the 30 continuous ‘reference’ series yields an annual mass loss of 0.58 m water equivalent (m w.e.) for the decade 1996–2005, which is more than twice the loss rate of the previous decade (1986–95: 0.25 m w.e.), and over four times the rate for the period 1976– 85 (0.14 m w.e.).

Overall, the cumulative average ice loss over the past six decades exceeds 20 m w.e. (Fig. 5.9), which is a dramatic ice wasting when compared to the global average ice thickness, which is estimated (by dividing estimated volume by area) to be between 100 m (IPCC 2007) and about 180 m (Ohmura, personal comm.). The average ice loss over that period of about 0.35 m w.e. per year exceeds the loss rates reconstructed from worldwide cumulative length changes for the time since the LIA (see Hoelzle et al. 2003) and is of the same order of magnitude as characteristic long-term mass changes during the past 2 000 years in the Alps (Haeberli and Holzhauser 2003). Based on the mass balance measurements, the annual contribution of glaciers and ice caps to the sea level rise is to be estimated at one-third of a millimetre between 1961 and 1990, with a doubling of this rate in the period from 1991 to 2004 (Kaser et al. 2006), and passing the one millimetre per year limit for the period 2000 to 2006. However, these values are to be considered first order estimates due to the rather small number of mass balance observations and their probably limited representativeness for the entire surface ice on land, outside the continental ice sheets. The vast ice loss over the past decades has already led to the splitting or disintegration of many glaciers within the observation network, e.g., Lower Curtis and Columbia 2057 (US), Chacaltaya (BO), Carèser (IT), Lewis (KE), Urumqihe (CN), and presents one of the major challenges for glacier monitoring in the 21st century (Paul et al. 2007). The massive downwasting of many glaciers over the past two decades, rather than dynamic retreat, has decoupled the glaciers horizontal extent (i.e. length, area) from current climate, so that glacier length or area change has definitely become a diminished climate indicator of non-linear behaviour. Under the present climate change scenarios (IPCC 2007), the ongoing trend of global and rapid, if not accelerating, glacier shrinkage on the century time scale is of non-periodic nature and may lead to the deglaciation of large parts of many mountain ranges in the coming decades (e.g., Zemp et al. 2006, Nesje et al. 2008).

[Iolo Morganwg] And this graph from an IPCC report shows glacier retreat began before any human influence on climate:

[Hermit] For most of the data the graph dates back to the 1700-1800 period. Given that human influence on climate surely began between 250 ky and 500 kyBP when we began burning areas to increase fertility and ease hunting (shown by increased incidence of carbon and organic residues in ice and ocean deposits), I am not sure how you plan to validate this claim, but look forward to watching you try.

[Iolo Morganwg] I am going to guess that you have read the article by Vincenzo Ferrara in ”Rivista di Meteorologia Aeronautica”, Vol XLII n. 1, Jan-Mar 1982. Vincenzo Ferrara was up until April 2008 the science advisor to the Italian Environment Minister.

[Hermit] I hadn't and it is cute, but the idea is not new. I remember that when I was 6 or so, my father explained to me that "forecasting" by predicting for tomorrow the same weather as today, or in a more sophisticated variation, by predicting the weather for tomorrow by predicting the same weather as had occurred on that day of the year in the past, by matching the weather today, with weather on this day in the year in the past, would beat any other form of forecasting system for short term weather phenomena - and that this class of hand waving is completely incompetent to predict anything; being a form of curve fitting to noise - and curves can be made to fit anything including noise. As this predated Vincenzo Ferrara by over 15 years, I guess he deserves precedence, even though he mentioned it only to debunk it. Then again, he is a very widely read man and he may have found it in some early work that predated both him and Vincenzo Ferrara.

Don't forget to have fun :-)

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

the.bricoleur

Adept

Posts: 341

Reputation: 7.35

Rate the.bricoleur

making sense of change

|

|

Re:The Flipping Point

« Reply #211 on: 2009-03-27 08:19:55 » |

|

Dear Hermit,

Apologies for the delay in responding to your post.

Quote from: Hermit on 2009-03-19 18:57:41 Meta Topic - Anthromorphic Atmospheric Composition Amendment

It is widely recognized that we have been responsible for massive changes in the surface of the planet since about 250kyBP and particularly in the last 5 to 7k5 yBP. If this is acknowledged, and it affected rainfall distribution (which it indubitably did), does this not imply that we affected the atmospheric composition, particulate levels, reflectivity levels, etc?

Of course we did.

Meta Topic - Late Modern Anthromorphic Atmospheric Composition Amendment

Most of Europe and the Americas and large areas in Asia, Africa and the Pacific were forested. Wars and the consequential need for timber for ships and charcoal for metallurgical processes, along with the need for wood for energy, drove deforestation in Europe. Colonial expansionism, population growth and the need for farmland and fuel drove deforestation in the rest of the world.

Areas which had been forested throughout the Holocene became grassland due to human and other species action and interaction. Consequential reductions in rainfall saw catastrophic top soil losses and desertification. Drainage systems killed bogs and swamps leaving the vegetation to rot and releasing vast amounts of Methane. Current palm plantation establishment is doing the same thing. Current clearing practices mean that it will take three hundred years of palm oil production to counterbalance the impact of the clearing needed to grow the palms. Given that we don't have a carbon offset for previous clearing efforts, the consequences were likely far worse.

It was only when we ran out of trees to burn that we started to burn coal on a significant scale.

So claims that man did not engage in massive atmospheric composition change, and particularly CO2 and Methane levels, prior to the modern era must necessarily fail. |

For the sake of clarity, I would like to note that my debate in this thread has been with regards to the anthropogenic global warming hypothesis.

Quote:| Atmospheric CO2 levels tell some of the story. Methane confirms and accentuates it. |

It is ridiculous to claim that methane is mainly from anthropogenic sources except for taxation purposes as in New Zealand (cows). The major source has to be where the highest mixing ratio can be found and that is in subarctic areas such as Siberia and Canada (and northern Sweden) which have vast forests and strong peat accumulation. Measurements from individual stations support this conclusion. There are several and Maona Loa is in no way representative besides showing a temporal trend line where CO2 already has been rather well mixed and its maximum mixing ratio has declined. The important fact when searching for the major sources of carbon release into the atmosphere is the spatial trends and especially the north-south one:

Quote:| Based on Ginko stomata, we entered the Holocene at about 280ppmv CO2. By the 1830s it had increased to about 284 ppmv. Today at over 390 ppmv we have increased atmospheric CO2 levels by about 100 ppmv or, translating this into a percentage, by 35%. Given that we now have rather good data on the carbon budget which supports the anthromorphic origin of these releases, claiming that this is not anthromorphic or that it doesn't affect the Atmospheric Greenhouse seems facile. Can you explain the mechanism whereby this sudden localized alteration of the laws of thermodynamics is alleged to occur? |

Let me start with my conclusion.

The emissions of CO2 from fossil fuel are not the determining CO2 contribution for changes in the isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2.

Please note that this conclusion is the only pertinent finding concerning the isotope changes which is relevant to determination of the cause of the recent rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration.

There is good reason to doubt the suggestion (e.g. by IPCC) that the steady base trend in recent rise to atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration is a result of accumulation of the anthropogenic emission in the air. A rise related to the anthropogenic emission should vary with the anthropogenic emission, but the steady rise does not. The anthropogenic emissions vary too much for them to be a likely cause of the steady rise of 1.5 ppm/year in atmospheric CO2 concentration that is independent of a temperature effect.

Please note that the annual anthropogenic emissions data need not vary with the atmospheric rise. Some of the emissions may be accounted in adjacent years so 2-year smoothing of the emissions data is warranted. And different nations may account their years from different start months so 3-year smoothing of the data is justifiable. However, the 5-year smoothing applied by the IPCC to get agreement between the anthropogenic emissions and the rise is not justifiable (they use it because 2-year, 3-year and 4-year smoothings fail to provide the agreement).

So, let me give you a model that is based on empirical data and is supported by the isotope changes.

The model is that water which entered deep ocean during the Medieval Warm Period (MWP) is now returning to the ocean surface and is inducing release of oceanic CO2 in response to altered ocean pH. This release could be expected to provide the steady increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration (of 1.5 ppm/year) that is observed to be independent of temperature variations.

I am very sceptical of the ice core data because I think they indicate falsely low and very smoothed values for past atmospheric CO2 concentrations. However, I do think the ice cores indicate long-term changes to past atmospheric CO2 concentrations. And the ice cores indicate that changes to atmospheric CO2 concentration follow changes to temperature by ~800 years. If this is correct, then the atmospheric CO2 concentration should now be rising as a result of the Medieval Warm Period (MWP).

This begs the question as to the cause of the ~800 year lag of atmospheric CO2 concentration after changes to temperature indicated by ice cores. And I suggest it is an effect of the thermohaline circulation.

The water now returning to the surface layer entered the deep ocean ~800 years ago during the MWP. Therefore, a release of oceanic CO2 in response to altered pH would concur with the ice core indications (assuming my acceptance of long-term trends in ice core data is correct).

Several studies have shown that the recent rise in atmospheric CO2 concentration varies around a base trend of 1.5 ppm/year. A decade ago Calder showed that the variations around the trend correlate to variations in mean global temperature (MGT): he called this his ‘CO2 thermometer’. Now, Ahlbeck has submitted a paper for publication that finds the same using recent data. Reasons for this ‘CO2 thermometer’ are not known but they probably result from changes to sea surface temperature.

So, there is strong evidence that MGT governs variations in the recent rise in atmospheric CO2 concentration but there is no clear evidence of the cause of the steady - and unwavering - base trend of 1.5 ppm/year.

Determination of cause and effect relationships is a severe problem when attempting to evaluate every aspect of the AGW hypothesis.

It is often claimed that ‘ocean acidification’ (i.e. change to the pH of the ocean surface layer that is reducing the alkalinity of the surface layer) is happening as a result of increased atmospheric CO2 concentration. However, the opposite is also possible because the deep ocean waters now returning to ocean surface could be altering the pH of the ocean surface layer with resulting release of CO2 from the ocean surface layer. Indeed, no actual release is needed because massive CO2 exchange occurs between the air and ocean surface each year and the changed pH would inhibit re-sequestration of the CO2 naturally released from ocean surface.

Ocean pH varies from about 7.90 to 8.20 at different geographical locations but along coasts there are much larger variations from 7.3 inside deep estuaries to 8.6 in productive coastal plankton blooms and 9.5 in tide pools. The pH is lowest in the most productive oceanic regions where upwellings of water from deep ocean occur.

It is thought that the average pH of the oceans decreased from 8.25 to 8.14 since the start of the industrial revolution (Jacobson M Z, 2005). And it should be noted that a decrease of pH from 8.2 to 8.1 corresponds with an increase of the CO2 in the air from 285.360 ppmv to 360.000 ppmv at solution equilibrium between air and ocean (calculations by Rorsch).

In other words, the ocean ‘acidification’ (estimated by Jacobson) is consistent with the change to atmospheric CO2 concentration for the estimated change to the solution equilibrium between air and ocean.

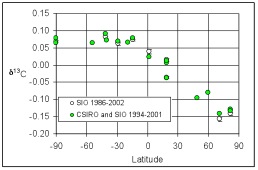

Also, the spatial distribution of 13C isotope changes in the atmosphere indicates that the source of those changes has an oceanic cause. The annual variations in latitude can be seen by looking at the profile of each year against its mean value as shown below. This indicates that the major source of the 13C isotope depletion comes from the far Northern Hemisphere; i.e. to the north of human habitation and industrial activity.

Variation of 13C with latitude compared to the yearly mean value

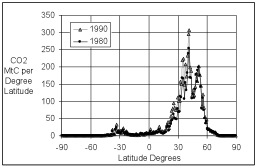

Estimated Atmospheric CO2 from fossil fuels. Source CDIAC

The fact of lowest ocean pH at positions of oceanic upwelling is a strong indication that the reduced upwelling is lowering the pH of the oceans. And the fact that observed oceanic pH change corresponds to the change to solution equilibrium between air and ocean indicates that re-sequestration of the CO2 naturally released from ocean surface has caused the observed change to atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration.

Hence, there is a coherent argument supported by empirical data that water now returning to the surface having entered deep ocean during the MWP may be inducing release of oceanic CO2 in response to altered pH, and this release could be expected to provide the steady increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration (of 1.5 ppm/year) that is observed to be independent of temperature variations.

Is that the true explanation? Possibly, but not certainly. There are other possibilities that fit the evidence, too.

I hope the above is what you wanted.

As for the remainder of your post, well, let's get past the above (and please, try to refrain from fobbing me off to wikipedia) and then we will know whether these changes are because of us, or us and something else, or something else ...

-iolo

|

|

|

|

|

the.bricoleur

Adept

Posts: 341

Reputation: 7.35

Rate the.bricoleur

making sense of change

|

|

Re:The Flipping Point

« Reply #212 on: 2009-03-27 08:35:47 » |

|

Dear Hermit and others,

I think that it is time for my contributions to this thread to cease.

I do acknowledge that human emissions are perturbing the natural cycle, but I am failing miserably to get the nuance of my position across successfully. We humans are doing an experiment on the atmosphere/surface system and we do not have a control planet to compare our results with. That makes it a bit tricky, but we have to manage somehow to try to understand what is happening.

This has been my purpose for participation.

However, with this recent round of posts I get the distinct impression that my contributions are neither valued or respected. I can only contribute to discussions as far as my understanding extends, and whilst perhaps hopefully limited, I do not think that such a limitation of knowledge needs to be likened to flat-earthers or other such tin hat wearers.

Quote:| Don't forget to have fun :-) |

Indeed. I seem to have forgotten this recently. Thanks for the reminder.

Kind regards,

-iolo

|

|

|

|

|

Fritz

Adept

Gender:

Posts: 1746

Reputation: 7.61

Rate Fritz

|

|

Re:The Flipping Point

« Reply #213 on: 2009-03-28 10:24:19 » |

|

Quote:[Iolo Morganwg]Dear Hermit and others,

I think that it is time for my contributions to this thread to cease. |

You got me reviewing and revisiting my views as does Hermit and the others. It would be a shame to me to loose your contribution; I am not comfortable with the main stream of information currently on the street.

1-I am currently of the notion that we are in a great deal of trouble.

2-I don't understand the scientific facts being presented

3-I have made use of climate models for Hydrological modeling and for River system modeling and definitely get how limited and how bad a job they can do if not calibrated, and we do not have the data to calibrate these climate models properly (environment Canada's models are based on 60 years) so they in my mind remain best guesses.

4-Books like 1421 the year China discovered the world, albeit for entertainment still present a climate that was very different from today with Viking settlements in Greenland and the Chinese sailors navigating under the Souther Cross and the North Star which is not possible with todays sea ice conditions.

I am still desperately trying to understand and everyones input is important and valuable to me.

Cheers

Fritz

|

Where there is the necessary technical skill to move mountains, there is no need for the faith that moves mountains -anon-

|

|

|

Blunderov

Archon

Gender:

Posts: 3160

Reputation: 8.06

Rate Blunderov

"We think in generalities, we live in details"

|

|

Re:The Flipping Point

« Reply #214 on: 2009-03-29 18:00:36 » |

|

Quote:[Iolo Morganwg]Dear Hermit and others,

I think that it is time for my contributions to this thread to cease. |

[Blunderov] I would like to add my voice to that of Fritz if I may. Iolo, in case there should be any doubt about it, we value your company and intellect immensely. This has proved to be a most vexing subject and I'm inclined to think that you are correct that it has been beaten to death. I know that this is a conclusion to which we have previously come. ( That, and that whatever the origin of climate change may be, it is probably already the case that the die is cast.) Perhaps we should lock the thread now.

Best Regards.

|

|

|

|

|

David Lucifer

Archon

Posts: 2642

Reputation: 8.38

Rate David Lucifer

Enlighten me.

|

|

The Civil Heretic

« Reply #215 on: 2009-03-29 19:01:29 » |

|

source: The New York Times

By NICHOLAS DAWIDOFF

FOR MORE THAN HALF A CENTURY the eminent physicist Freeman Dyson has quietly resided in Prince ton, N.J., on the wooded former farmland that is home to his employer, the Institute for Advanced Study, this country’s most rarefied community of scholars. Lately, however, since coming “out of the closet as far as global warming is concerned,” as Dyson sometimes puts it, there has been noise all around him. Chat rooms, Web threads, editors’ letter boxes and Dyson’s own e-mail queue resonate with a thermal current of invective in which Dyson has discovered himself variously described as “a pompous twit,” “a blowhard,” “a cesspool of misinformation,” “an old coot riding into the sunset” and, perhaps inevitably, “a mad scientist.” Dyson had proposed that whatever inflammations the climate was experiencing might be a good thing because carbon dioxide helps plants of all kinds grow. Then he added the caveat that if CO2 levels soared too high, they could be soothed by the mass cultivation of specially bred “carbon-eating trees,” whereupon the University of Chicago law professor Eric Posner looked through the thick grove of honorary degrees Dyson has been awarded — there are 21 from universities like Georgetown, Princeton and Oxford — and suggested that “perhaps trees can also be designed so that they can give directions to lost hikers.” Dyson’s son, George, a technology historian, says his father’s views have cooled friendships, while many others have concluded that time has cost Dyson something else. There is the suspicion that, at age 85, a great scientist of the 20th century is no longer just far out, he is far gone — out of his beautiful mind.

But in the considered opinion of the neurologist Oliver Sacks, Dyson’s friend and fellow English expatriate, this is far from the case. “His mind is still so open and flexible,” Sacks says. Which makes Dyson something far more formidable than just the latest peevish right-wing climate-change denier. Dyson is a scientist whose intelligence is revered by other scientists — William Press, former deputy director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory and now a professor of computer science at the University of Texas, calls him “infinitely smart.” Dyson — a mathematics prodigy who came to this country at 23 and right away contributed seminal work to physics by unifying quantum and electrodynamic theory — not only did path-breaking science of his own; he also witnessed the development of modern physics, thinking alongside most of the luminous figures of the age, including Einstein, Richard Feynman, Niels Bohr, Enrico Fermi, Hans Bethe, Edward Teller, J. Robert Oppenheimer and Edward Witten, the “high priest of string theory” whose office at the institute is just across the hall from Dyson’s. Yet instead of hewing to that fundamental field, Dyson chose to pursue broader and more unusual pursuits than most physicists — and has lived a more original life.

Among Dyson’s gifts is interpretive clarity, a penetrating ability to grasp the method and significance of what many kinds of scientists do. His thoughts about how science works appear in a series of lucid, elegant books for nonspecialists that have made him a trusted arbiter of ideas ranging far beyond physics. Dyson has written more than a dozen books, including “Origins of Life” (1999), which synthesizes recent discoveries by biologists and geologists into an evaluation of the double-origin hypothesis, the possibility that life began twice; “Disturbing the Universe” (1979) tries among other things to reconcile science and humanity. “Weapons and Hope” (1984) is his meditation on the meaning and danger of nuclear weapons that won a National Book Critics Circle Award. Dyson’s books display such masterly control of complex matters that smart young people read him and want to be scientists; older citizens finish his books and feel smart.

Yet even while probing and sifting, Dyson is always whimsically gazing into the beyond. As a boy he sketched plans for English rocket ships that could explore the stars, and then, in midlife, he helped design an American spacecraft to be powered by exploding atomic bombs — a secret Air Force project known as Orion. Dyson remains an armchair astronaut who speculates with glee about the coming of cheap space travel, when families can leave an overcrowded earth to homestead on asteroids and comets, swooping around the universe via solar sail craft. Dyson is convinced that our current “age of computers” will soon give way to “the age of domesticated biotechnology.” Bio-tech, he writes in his book, “Infinite in All Directions” (1988), “offers us the chance to imitate nature’s speed and flexibility,” and he imagines the furniture and art that people will “grow” for themselves, the pet dinosaurs they will “grow” for their children, along with an idiosyncratic menagerie of genetically engineered cousins of the carbon-eating tree: termites to consume derelict automobiles, a potato capable of flourishing on the dry red surfaces of Mars, a collision-avoiding car.

These ideas attract derision similar to Dyson’s essays on climate change, but he is an undeterred octogenarian futurist. “I don’t think of myself predicting things,” he says. “I’m expressing possibilities. Things that could happen. To a large extent it’s a question of how badly people want them to. The purpose of thinking about the future is not to predict it but to raise people’s hopes.” Formed in a heretical and broad-thinking tradition of British public intellectuals, Dyson left behind a brooding England still stricken by two bloody world wars to become an optimistic American immigrant with tremendous faith in the creative imagination’s ability to invent technologies that would overcome any predicament. And according to the physicist and former Caltech president Marvin Goldberger, Dyson is himself the living embodiment of that kind of ingenuity. “You point Freeman at a problem and he’ll solve it,” Goldberger says. “He’s extraordinarily powerful.” Dyson seems to see the world as an interdisciplinary set of problems out there for him to evaluate. Climate change is the big scientific issue of our time, so naturally he finds it irresistible. But to Dyson this is really only one more charged conundrum attracting his interest just as nuclear weapons and rural poverty have. That is to say, he is a great problem-solver who is not convinced that climate change is a great problem.

Dyson is well aware that “most consider me wrong about global warming.” That educated Americans tend to agree with the conclusion about global warming reached earlier this month at the International Scientific Conference on Climate Change in Copenhagen (“inaction is inexcusable”) only increases Dyson’s resistance. Dyson may be an Obama-loving, Bush-loathing liberal who has spent his life opposing American wars and fighting for the protection of natural resources, but he brooks no ideology and has a withering aversion to scientific consensus. The Nobel physics laureate Steven Weinberg admires Dyson’s physics — he says he thinks the Nobel committee fleeced him by not awarding his work on quantum electrodynamics with the prize — but Weinberg parts ways with his sensibility: “I have the sense that when consensus is forming like ice hardening on a lake, Dyson will do his best to chip at the ice.”

Dyson says he doesn’t want his legacy to be defined by climate change, but his dissension from the orthodoxy of global warming is significant because of his stature and his devotion to the integrity of science. Dyson has said he believes that the truths of science are so profoundly concealed that the only thing we can really be sure of is that much of what we expect to happen won’t come to pass. In “Infinite in All Directions,” he writes that nature’s laws “make the universe as interesting as possible.” This also happens to be a fine description of Dyson’s own relationship to science. In the words of Avishai Margalit, a philosopher at the Institute for Advanced Study, “He’s a consistent reminder of another possibility.” When Dyson joins the public conversation about climate change by expressing concern about the “enormous gaps in our knowledge, the sparseness of our observations and the superficiality of our theories,” these reservations come from a place of experience. Whatever else he is, Dyson is the good scientist; he asks the hard questions. He could also be a lonely prophet. Or, as he acknowledges, he could be dead wrong.

IT WAS FOUR YEARS AGO that Dyson began publicly stating his doubts about climate change. Speaking at the Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future at Boston University, Dyson announced that “all the fuss about global warming is grossly exaggerated.” Since then he has only heated up his misgivings, declaring in a 2007 interview with Salon.com that “the fact that the climate is getting warmer doesn’t scare me at all” and writing in an essay for The New York Review of Books, the left-leaning publication that is to gravitas what the Beagle was to Darwin, that climate change has become an “obsession” — the primary article of faith for “a worldwide secular religion” known as environmentalism. Among those he considers true believers, Dyson has been particularly dismissive of Al Gore, whom Dyson calls climate change’s “chief propagandist,” and James Hansen, the head of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York and an adviser to Gore’s film, “An Inconvenient Truth.” Dyson accuses them of relying too heavily on computer-generated climate models that foresee a Grand Guignol of imminent world devastation as icecaps melt, oceans rise and storms and plagues sweep the earth, and he blames the pair’s “lousy science” for “distracting public attention” from “more serious and more immediate dangers to the planet.”

A particularly distressed member of that public was Dyson’s own wife, Imme, who, after seeing the film in a local theater with Dyson when it was released in 2006, looked at her husband out on the sidewalk and, with visions of drowning polar bears still in her eyes, reproached him: “Everything you told me is wrong!” she cried.

“The polar bears will be fine,” he assured her.

Not long ago Dyson sat in his institute office, a chamber so neat it reminds Dyson’s friend, the writer John McPhee, of a Japanese living room. On shelves beside Dyson were books about stellar evolution, viruses, thermodynamics and terrorism. “The climate-studies people who work with models always tend to overestimate their models,” Dyson was saying. “They come to believe models are real and forget they are only models.” Dyson speaks in calm, clear tones that carry simultaneous evidence of his English childhood, the move to the United States after completing his university studies at Cambridge and more than 50 years of marriage to the German-born Imme, but his opinions can be barbed, especially when a conversation turns to climate change. Climate models, he says, take into account atmospheric motion and water levels but have no feeling for the chemistry and biology of sky, soil and trees. “The biologists have essentially been pushed aside,” he continues. “Al Gore’s just an opportunist. The person who is really responsible for this overestimate of global warming is Jim Hansen. He consistently exaggerates all the dangers.”

Dyson agrees with the prevailing view that there are rapidly rising carbon-dioxide levels in the atmosphere caused by human activity. To the planet, he suggests, the rising carbon may well be a MacGuffin, a striking yet ultimately benign occurrence in what Dyson says is still “a relatively cool period in the earth’s history.” The warming, he says, is not global but local, “making cold places warmer rather than making hot places hotter.” Far from expecting any drastic harmful consequences from these increased temperatures, he says the carbon may well be salubrious — a sign that “the climate is actually improving rather than getting worse,” because carbon acts as an ideal fertilizer promoting forest growth and crop yields. “Most of the evolution of life occurred on a planet substantially warmer than it is now,” he contends, “and substantially richer in carbon dioxide.” Dyson calls ocean acidification, which many scientists say is destroying the saltwater food chain, a genuine but probably exaggerated problem. Sea levels, he says, are rising steadily, but why this is and what dangers it might portend “cannot be predicted until we know much more about its causes.”

For Hansen, the dark agent of the looming environmental apocalypse is carbon dioxide contained in coal smoke. Coal, he has written, “is the single greatest threat to civilization and all life on our planet.” Hansen has referred to railroad cars transporting coal as “death trains.” Dyson, on the other hand, told me in conversations and e-mail messages that “Jim Hansen’s crusade against coal overstates the harm carbon dioxide can do.” Dyson well remembers the lethal black London coal fog of his youth when, after a day of visiting the city, he would return to his hometown of Winchester with his white shirt collar turned black. Coal, Dyson says, contains “real pollutants” like soot, sulphur and nitrogen oxides, “really nasty stuff that makes people sick and looks ugly.” These are “rightly considered a moral evil,” he says, but they “can be reduced to low levels by scrubbers at an affordable cost.” He says Hansen “exploits” the toxic elements of burning coal as a way of condemning the carbon dioxide it releases, “which cannot be reduced at an affordable cost, but does not do any substantial harm.”

Science is not a matter of opinion; it is a question of data. Climate change is an issue for which Dyson is asking for more evidence, and leading climate scientists are replying by saying if we wait for sufficient proof to satisfy you, it may be too late. That is the position of a more moderate expert on climate change, William Chameides, dean of the Nicholas School of the Environment and Earth Sciences at Duke University, who says, “I don’t think it’s time to panic,” but contends that, because of global warming, “more sea-level rise is inevitable and will displace millions; melting high-altitude glaciers will threaten the food supplies for perhaps a billion or more; and ocean acidification could undermine the food supply of another billion or so.” Dyson strongly disagrees with each of these points, and there follows, as you move back and forth between the two positions, claims and counterclaims, a dense thicket of mitigating scientific indicators that all have the timbre of truth and the ring of potential plausibility. One of Dyson’s more significant surmises is that a warming climate could be forestalling a new ice age. Is he wrong? No one can say for sure. Beyond the specific points of factual dispute, Dyson has said that it all boils down to “a deeper disagreement about values” between those who think “nature knows best” and that “any gross human disruption of the natural environment is evil,” and “humanists,” like himself, who contend that protecting the existing biosphere is not as important as fighting more repugnant evils like war, poverty and unemployment.

Embedded in all of Dyson’s strong opinions about public policy is a dual spirit of social activism and uneasiness about class dating all the way back to Winchester, where he was raised in the 1920s and ’30s by his father, George Dyson, the son of a Yorkshire blacksmith. George was the music instructor at Winchester College, an old and prestigious secondary school, and a composer. Dyson’s mother, Mildred Atkey, came from a more prosperous Wimbledon family that had its own tennis court. Together they raised Dyson and his sister, Alice, in what Dyson calls a “watered-down Church of England Christianity” that regarded religion as a guide to living rather than any system of belief. The emphasis on tolerance, charity and community — and the free time afforded by the luxury of four servants — led Mildred to organize a club for teenage girls and a birth-control clinic. These institutions meshed uneasily with her patrician Victorian sensibilities. The girls were never, Dyson says, “considered equals,” and Mildred told him with amusement about the young mother who walked in carrying a red-headed infant. “What a beautiful baby,” Mildred reported saying. “Does he take after his father?”

“Oh, I couldn’t tell you, Mum,” came the reply. “He kept his hat on.”

Winchester is a medieval town in which, Dyson writes, he felt that everyone was looking backward, mourning all the young men lost to one world war while silently anticipating his own generation’s impending demise. He renounced the nostalgia, the servants, the hard-line social castes. But what he liked about growing up in England was the landscape. The country’s successful alteration of wilderness and swamp had created a completely new green ecology, allowing plants, animals and humans to thrive in “a community of species.” Dyson has always been strongly opposed to the idea that there is any such thing as an optimal ecosystem — “life is always changing” — and he abhors the notion that men and women are something apart from nature, that “we must apologize for being human.” Humans, he says, have a duty to restructure nature for their survival.

All this may explain why the same man could write “we live on a shrinking and vulnerable planet which our lack of foresight is rapidly turning into a slum” and yet gently chide the sort of Americans who march against coal in Washington. Dyson has great affection for coal and for one big reason: It is so inexpensive that most of the world can afford it. “There’s a lot of truth to the statement Greens are people who never had to worry about their grocery bills,” he says. (“Many of these people are my friends,” he will also tell you.) To Dyson, “the move of the populations of China and India from poverty to middle-class prosperity should be the great historic achievement of the century. Without coal it cannot happen.” That said, Dyson sees coal as the interim kindling of progress. In “roughly 50 years,” he predicts, solar energy will become cheap and abundant, and “there are many good reasons for preferring it to coal.”

THE WORDS COLLEAGUES COMMONLY use to describe Dyson include “unassuming” and “modest,” and he seems the very embodiment of Newton’s belief that a man should strive for simplicity and avoid confusion in life. Dyson has been in residence at the institute since 1953, a time when Albert Einstein shared his habit of walking to work there, which Dyson still does seven days a week, to write on a computer and solve any problems that come across his desk with paper and pencil. (In his prime, legend held that he never used the eraser.) He and Imme have spent 51 happy years together in the same house, a white clapboard just over the garden fence from the stucco affair once inhabited by their former neighbors, the Oppenheimers. On some Sundays the Dysons pile into a car still decorated with an Obama bumper sticker and drive to running races, at which Dyson can be found at the finish line loudly cheering for the 72-year-old Imme, a master’s marathon champion. On many other weekends, they visit some of their 16 grandchildren. During the holiday season the Dysons routinely attend five parties a week, cocktail-soiree sprints at which guests tend to find him open-minded and shy: when friends’ wives give him a hug, he blushes. One of Dyson’s daughters, the Internet vizier Esther Dyson, says her father raised her without a television so she would read more, and has always been “just as interested in talking to” the latest graduate student to make the pilgrimage to Princeton “as he is the famous person at the next table.” Oliver Sacks says that Dyson has “a genius for friendship.”

But the truth is that Dyson is an elusive particle. To Edward Witten it is clear that Dyson has little use for string theory, the cutting-edge “theory of everything” that links quantum mechanics and relativity in an effort to describe no less than the nature of all things. Even so, Witten admits that there is a fever-dream quality to his conversations with Dyson: “I don’t always know what he disagrees with entirely. His attitudes are complicated. There are many layers.” Other people can be similarly intrigued and baffled. When I began spending time with Dyson and asked who his close friends are, the only name he mentioned was John McPhee’s, which surprised McPhee since he said he doesn’t often speak with Dyson even though McPhee teaches nearby at Princeton University. All six of Dyson’s children describe him as a loving, intensely devoted father and yet also suggest that this is a parent with, in the words of his son, George, core parts of him that have always seemed “remote.” William Press said he finds Dyson to be both a “deep” and “magnificently laudable person” and also mysterious and inscrutable, a man with contrarian opinions that Press suspects may be motivated by “a darker side he’s determined the world isn’t going to see.” When I asked Sacks what he thought about all this, he said that “a favorite word of Freeman’s about doing science and being creative is the word ‘subversive.’ He feels it’s rather important not only to be not orthodox, but to be subversive, and he’s done that all his life.”

Dyson says it’s only principle that leads him to question global warming: “According to the global-warming people, I say what I say because I’m paid by the oil industry. Of course I’m not, but that’s part of their rhetoric. If you doubt it, you’re a bad person, a tool of the oil or coal industry.” Global warming, he added, “has become a party line.”

What may trouble Dyson most about climate change are the experts. Experts are, he thinks, too often crippled by the conventional wisdom they create, leading to the belief that “they know it all.” The men he most admires tend to be what he calls “amateurs,” inventive spirits of uncredentialed brilliance like Bernhard Schmidt, an eccentric one-armed alcoholic telescope-lens designer; Milton Humason, a janitor at Mount Wilson Observatory in California whose native scientific aptitude was such that he was promoted to staff astronomer; and especially Darwin, who, Dyson says, “was really an amateur and beat the professionals at their own game.” It’s a point of pride with Dyson that in 1951 he became a member of the physics faculty at Cornell and then, two years later, moved on to the Institute for Advanced Study, where he became an influential man, a pragmatist providing solutions to the military and Congress, and also the 2000 winner of the $1 million Templeton Prize for broadening the understanding of science and religion, an award previously given to Mother Teresa and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn — all without ever earning a Ph.D. Dyson may, in fact, be the ultimate outsider-insider, “the world’s most civil heretic,” as the classical composer Paul Moravec, the artistic consultant at the institute, says of him.

Climate-change specialists often speak of global warming as a matter of moral conscience. Dyson says he thinks they sound presumptuous. As he warned that day four years ago at Boston University, the history of science is filled with those “who make confident predictions about the future and end up believing their predictions,” and he cites examples of things people anticipated to the point of terrified certainty that never actually occurred, ranging from hellfire, to Hitler’s atomic bomb, to the Y2K millennium bug. “It’s always possible Hansen could turn out to be right,” he says of the climate scientist. “If what he says were obviously wrong, he wouldn’t have achieved what he has. But Hansen has turned his science into ideology. He’s a very persuasive fellow and has the air of knowing everything. He has all the credentials. I have none. I don’t have a Ph.D. He’s published hundreds of papers on climate. I haven’t. By the public standard he’s qualified to talk and I’m not. But I do because I think I’m right. I think I have a broad view of the subject, which Hansen does not. I think it’s true my career doesn’t depend on it, whereas his does. I never claim to be an expert on climate. I think it’s more a matter of judgement than knowledge.”

Reached by telephone, Hansen sounds annoyed as he says, “There are bigger fish to fry than Freeman Dyson,” who “doesn’t know what he’s talking about.” In an e-mail message, he adds that his own concern about global warming is not based only on models, and that while he respects the “open-mindedness” of Dyson, “if he is going to wander into something with major consequences for humanity and other life on the planet, then he should first do his homework — which he obviously has not done on global warming.”

When Dyson hears about this, he looks, if possible, like a person taking the longer view. He is a short, sinewy man with strawlike filaments of excitable gray hair that make him resemble an upside-down broom. Every day he dresses with the same frowzy Oxbridge formality in L. L. Bean khaki trousers (his daughter Mia is a minister in Maine), a tweed sport coat, a necktie (most often one made for him, he says, by another daughter, Emily, many years ago “in the age of primary colors”) and wool sweater-vests. On cold days he wears a second vest, one right over the other, and the effect is like a window with two sets of curtains. His smile is the real window, a delighted beam that appears to float free from his face, strangely dynamic with its electric ears and quantum nose, and his laugh is so hearty it shakes him. The smile and laughter have the effect of softening Dyson’s formality, transforming him into a sage and friendly elf, and also reminding those he talks with that he has spent a lifetime immersed in efforts to find what he considers humane solutions to dire problems, whose controversial gloss never seems to agitate him. His eyes are murky gray, and whatever he’s thinking beyond what he says, the eyes never betray.

A FORMATIVE MOMENT in Dyson’s life that pushed him in an apostatical direction happened in 1932, when, at age 8, he was sent off to boarding school at Twyford. By then he was a prodigy “already obsessed” with mathematics. (His older sister Alice, a retired social worker still living in Winchester, remembers how her brother “used to lie on the nursery floor working out how many atoms there were in the sun. He was perhaps 4.”) At Twyford — like George Orwell, who was flogged, starved and humiliated by masters and bigger boys at St. Cyprian’s — Dyson says he felt brutalized by a whip-wielding headmaster who offered no science classes, favoring Latin, and by a clique of athletes who liked to rub sandpaper on the faces of the smaller children. “In those days it was unthinkable that parents would come to see what was going on,” Dyson says. “My parents lived only three miles away. They never came to visit. It wasn’t done.” Dyson took comfort in climbing tall trees, reading “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” which gave him a first sense of America as a more “exciting place where all sorts of weird things could happen,” and Jules Verne’s comic science-fiction descriptions of more “crazy Americans” bound for the moon. His primary consolation, however, was the science society he founded with a few friends. Dyson would later reflect that from then on he saw science as “a territory of freedom and friendship in the midst of tyranny and hatred.”

Four years later he entered Winchester College, well known for academic rigor, and he thrived. On his own in the school library, he read mathematical works in French and German and, at age 13, taught himself calculus from an Encyclopedia Britannica entry. “I remember thinking, Is that it?” he says. “People had been telling me how hard it was.” Another day in the library he discovered “Daedalus, or Science and the Future,” by the biologist J. B. S. Haldane, who said that “the thing that has not been is the thing that shall be; that no beliefs, no values, no institutions are safe,” an appealing outlook to Dyson, who had found his muse. “Haldane was even more of a heretic than I am,” he says. “He really loved to make people angry.” It wasn’t all science. On trips into London he spent entire days in bookstores where William Blake “got hold of me. What I really liked was he was a really rebellious spirit who always said the opposite of what everybody else believed.”

That defiant sensibility hardened further when the second war with Germany began. Dyson says he can “remember so vividly lying in bed at age 15, absolutely enjoying hearing the bombs go off with a wonderful crunching noise. I said, ‘That’s the sound of the British Empire crumbling.’ I had a sense that the British Empire was evil. The fact that I might get hit didn’t register at all. I think that’s a natural state of mind for a 15-year-old. I somehow got over it.” At Cambridge, Dyson attended all the advanced mathematics lectures and climbed roofs at night during blackouts. By the end of the school year in 1943, which Dyson celebrated by pushing his wheelchairbound classmate, Oscar Hahn, the 55 miles home to London in one 17-hour day, Dyson was fully formed as a person of strong, frequently rebellious beliefs, someone who would always go his own way.

During World War II, Dyson worked for the Royal Air Force at Bomber Command, calculating the most effective ways to deploy pilots, some of whom he knew would die. Dyson says he was “sickened” and “depressed” that many more planes were going down than needed to because military leadership relied on misguided institutional mythologies rather than statistical studies. Even more upsetting, Dyson writes in “Weapons and Hope,” he became an expert on “how to murder most economically another hundred thousand people.” This work, Dyson told the writer Kenneth Brower, created an “emptiness of the soul.”

Then came two blinding flashes of light. Dyson’s reaction to Hiroshima and Nagasaki was complicated. Like many physicists, Dyson has always loved explosions, and, of course, uncovering the secrets of nature is the first motivation of science. When he was interviewed for the 1980 documentary “The Day After Trinity,” Dyson addressed the seduction: “I felt it myself, the glitter of nuclear weapons. It is irresistible if you come to them as a scientist. To feel it’s there in your hands. To release the energy that fuels the stars. To let it do your bidding. And to perform these miracles, to lift a million tons of rock into the sky, it is something that gives people an illusion of illimitable power, and it is in some ways responsible for all our troubles, I would say, this what you might call ‘technical arrogance’ that overcomes people when they see what they can do with their minds.”

Eventually, Dyson would be sure nuclear weapons were the worst evil. But in 1945, drawn to these irreducible components of life, Dyson left mathematics and took up physics. Still, he did not want to be another dusty Englishman toiling alone in a dim Cambridge laboratory. Since childhood, some part of him had always known that the “Americans held the future in their hands and that the smart thing for me to do would be to join them.” That the United States was now the country of Einstein and Oppenheimer was reason enough to go, but Dyson’s sister Alice says that “he escaped to America so he could make his own life,” removed from the shadow of his now famous musical father. “I know how he felt,” says Oliver Sacks, who came to New York not long after medical school. “I was the fifth Dr. Sacks in my family. I felt it was time to get out and find a place of my own.”

In 1947, Dyson enrolled as a doctoral candidate at Cornell, studying with Hans Bethe, who had the reputation of being the greatest problem-solver in physics. Alice Dyson says that once in Ithaca, her brother “became so much more human,” and Dyson does not disagree. “I really felt it was quite amazing how accepted I was,” he says. “In 1963, I’d only been a U.S. citizen for about five years, and I was testifying to the Senate, representing the Federation of American Scientists in favor of the nuclear-test-ban treaty.”

After sizing him up over a few meals, Bethe gave Dyson a problem and told him to come back in six months. “You just sit down and do it,” Dyson told me. “It’s probably the hardest work you’ll do in your life. Without having done that, you’ve never understood what science is all about.” This smaller problem was part of a much larger one inherited from Einstein, among others, involving the need for a theory to describe the behavior of atoms and electrons emitting and absorbing light. Put another way, it was the question of how to move physics forward, creating agreement among the disparate laws of atomic structure, radiation, solid-state physics, plasma physics, maser and laser technology, optical and microwave spectroscopy, electronics and chemistry. Many were working on achieving this broad rapport, including Julian Schwinger at Harvard University; a Japanese physicist named Shinichiro Tomonaga, whose calculations arrived in America from war-depleted Kyoto on cheap brown paper; and Feynman, also at Cornell, a man so brilliant he did complex calculations in his head. Initially, Bethe asked Dyson to make some difficult measurements involving electrons. But soon enough Dyson went further.

The breakthrough came on summer trips Dyson made in 1948, traveling around America by Greyhound bus and also, for four days, in a car with Feynman. Feynman was driving to Albuquerque, and Dyson joined him just for the pleasure of riding alongside “a unique person who had such an amazing combination of gifts.” The irrepressible Feynman and the “quiet and dignified English fellow,” as Feynman described Dyson, picked up gypsy hitchhikers; took shelter from an Oklahoma flood in the only available hotel they could find, a brothel, where Feynman pretended to sleep and heard Dyson relieve himself in their room sink rather than risk the common bathroom in the hall; spoke of Feynman’s realization that he had enjoyed military work on the Manhattan Project too much and therefore could do it no more; and talked about Feynman’s ideas in a way that made Dyson forever understand what the nature of true genius is. Dyson wanted to unify one big theory; Feynman was out to unify all of physics. Inspired by this and by a mesmerizing sermon on nonviolence that Dyson happened to hear a traveling divinity student deliver in Berkeley, Dyson sat aboard his final Greyhound of the summer, heading East. He had no pencil or paper. He was thinking very hard. On a bumpy stretch of highway, long after dark, somewhere out in the middle of Nebraska, Dyson says, “Suddenly the physics problem became clear.” What Feynman, Schwinger and Tomonaga were doing was stylistically different, but it was all “fundamentally the same.”

Dyson is always effacing when discussing his work — he has variously called himself a tinkerer, a clean-up man and a bridge builder who merely supplied the cantilevers linking other men’s ideas. Bethe thought more highly of him. “He is the best I have ever had or observed,” Bethe wrote in a letter to Oppenheimer, who invited Dyson to the institute for an initial fellowship. There, with Einstein indifferent to him and the chain-smoking Oppenheimer openly doubting Dyson’s physics, Dyson wrote his renowned paper “The Radiation Theories of Tomonaga, Schwinger and Feynman.” Oppenheimer sent Dyson a note: “Nolo contendere — R.O.” If you could do that in a year, who needed a Ph.D.? The institute was perfect for him. He could work all morning and, as he wrote to his parents, in the afternoons go for walks in the woods to see “strange new birds, insects and plants.” It was, Dyson says, the happiest sustained moment in his life. It was also the last great discovery he would make in physics.

Other physicists quietly express disappointment that Dyson didn’t do more to advance the field, that he wasted his promise. “He did some things in physics after the heroic work in 1949, but not as much as I would have expected for someone so off-the-scale smart,” one physicist says. From others there are behind-the-study-door speculations that perhaps Dyson lacked the necessary “killer instinct”; or that he was discouraged by Enrico Fermi, who told him that his further work on quantum electrodynamics was unpromising; or “that he never felt he could approach Feynman’s brilliance.” Dyson shakes his head. “I’ve always enjoyed what I was doing quite independently of whether it was important or not,” he says. “I think it’s almost true without exception if you want to win a Nobel Prize, you should have a long attention span, get ahold of some deep and important problem and stay with it for 10 years. That wasn’t my style.”

DYSON HAD ALWAYS wanted “a big family.” In 1950, after knowing the brilliant mathematician Verena Huber for three weeks, Dyson proposed. They married, Esther and George were born, but the union didn’t last. “She was more interested in mathematics than in raising kids,” he says. By 1958, Dyson had married Imme — he has the brains, she has the legs, the Dysons like to joke — and they settled “in this snobbish little town,” as he calls Princeton. They had four more daughters. All six Dysons describe eventful child hoods with people like Feynman coming by for meals. Their father, meanwhile, was always preaching the virtues of boredom: “Being bored is the only time you are creative” was his thinking. George recalls groups of physicists closing doors and saying, “No children.” Through the keyhole George would hear words that gave him thermonuclear nightmares. All of them remember Dyson coming home, arms filled with bouquets of new appliances to make Imme’s life easier: an automatic ironing machine; a snowblower; one of the first microwave ovens in Princeton.

Beginning in the late ’50s, Dyson spent months in California, on the La Jolla campus of General Atomics, a peacetime Los Alamos, where scientists were seeking progressive uses for nuclear energy. After a challenge from Edward Teller to build a completely safe reactor, Dyson and Ted Taylor patented the Triga, a small isotope machine that is still used for medical diagnostics in hospitals. Then came the Orion rocket, designed so successions of atomic bombs would explode against the spaceship’s massive pusher plate, propelling astronauts toward the moon and beyond. “For me, Orion meant opening up the whole solar system to life,” he says. “It could have changed history.” Dyson says he “thought of Orion as the solution to a problem. With one trip we’d have got rid of 2,000 bombs.” But instead, he lent his support to the nuclear-test-ban treaty with the U.S.S.R., which killed Orion. “This was much more serious than Orion ever would be,” he said later. Dyson’s powers of concentration were so formidable in those years that George remembers sitting with his father and “he’d just disappear.”

One idea pulsing through his mind was a thought experiment that he published in the journal Science in 1959 that described massive energy-collecting shells that could encircle a star and capture solar energy. This was Dyson’s initial response to his insight that earthbound reserves of fossil fuels were limited. The structures are known as Dyson Spheres to science-fiction authors like Larry Niven and by the writers of an episode of “Star Trek” — the only engineers so far to succeed in building one.

This was an early indication of Dyson’s growing interest in what one day would be called climate studies. In 1976, Dyson began making regular trips to the Institute for Energy Analysis in Oak Ridge, Tenn., where the director, Alvin Weinberg, was in the business of investigating alternative sources of power. Charles David Keeling’s pioneering measurements at Mauna Loa, Hawaii, showed rapidly increasing carbon-dioxide levels in the atmosphere; and in Tennessee, Dyson joined a group of meteorologists and biologists trying to understand the effects of carbon on the Earth and air. He was now becoming a climate expert. Eventually Dyson published a paper titled “Can We Control the Carbon Dioxide in the Atmosphere?” His answer was yes, and he added that any emergency could be temporarily thwarted with a “carbon bank” of “fast-growing trees.” He calculated how many trees it would take to remove all carbon from the atmosphere. The number, he says, was a trillion, which was “in principle quite feasible.” Dyson says the paper is “what I’d like people to judge me by. I still think everything it says is true.”

Eventually he would embrace another idea: the notorious carbon-eating trees, which would be genetically engineered to absorb more carbon than normal trees. Of them, he admits: “I suppose it sounds like science fiction. Genetic engineering is politically unpopular in the moment.”

In the 1970s, Dyson participated in other climate studies conducted by Jason, a small government-financed group of the country’s finest scientists, whose members gather each summer near San Diego to work on (often) classified (usually) scientific dilemmas of (frequently) military interest to the government. Dyson has, as he admits, a restless nature, and by the time many scientists were thinking about climate, Dyson was on to other problems. Often on his mind were proposals submitted by the government to Jason. “Mainly we kill stupid projects,” he says.

Some scientists refuse military work on the grounds that involvement in killing is sin. Dyson was opposed to the wars in Vietnam and Iraq, but not to generals. He had seen in England how a military more enlightened by quantitative analysis could have better protected its men and saved the lives of civilians. “I always felt the worse the situation was, the more important it was to keep talking to the military,” he says. Over the years he says he pushed the rejection of the idea of dropping atomic bombs on North Vietnam and solved problems in adaptive optics for telescopes. Lately he has been “trying to help the intelligence people be aware of what the bad guys may be doing with biology.” Dyson thinks of himself as “fighting for peace,” and Joel Lebowitz, a Rutgers physicist who has known Dyson for 50 years, says Dyson lives up to that: “He works for Jason and he’s out there demonstrating against the Iraq war.”

At Jason, taking problems to Dyson is something of a parlor trick. A group of scientists will be sitting around the cafeteria, and one will idly wonder if there is an integer where, if you take its last digit and move it to the front, turning, say, 112 to 211, it’s possible to exactly double the value. Dyson will immediately say, “Oh, that’s not difficult,” allow two short beats to pass and then add, “but of course the smallest such number is 18 digits long.” When this happened one day at lunch, William Press remembers, “the table fell silent; nobody had the slightest idea how Freeman could have known such a fact or, even more terrifying, could have derived it in his head in about two seconds.” The meal then ended with men who tend to be described with words like “brilliant,” “Nobel” and “MacArthur” quietly retreating to their offices to work out what Dyson just knew.

These days, most of what consumes Dyson is his writing. In a recent article, he addressed the issue of reductionist thinking obliquely, as a question of perspective. Birds, he wrote, “fly high in the air and survey broad vistas.” Frogs like him “live in the mud below and see only the flowers that grow nearby.” Whether the topic is government work, string theory or climate change, Dyson seems opposed to science making enormous gestures. The physicist Douglas Eardley, who works with Dyson at Jason, says: “He’s always against the big monolithic projects, the Battlestar Galacticas. He prefers spunky little Mars rovers.” Dyson has been hostile to the Star Wars missile-defense system, the Space Station, the Hubble telescope and the superconducting super collider, which he says he opposed because “it’s just out of proportion.” Steven Weinberg, the Nobel physics laureate who often disagrees with Dyson on these matters, says: “Some things simply have to be done in a large way. They’re very expensive. That’s big science. Get over it.”

Around the Institute for Advanced Study, that intellectual Arcadia where the blackboards have signs on them that say Do Not Erase, Dyson is quietly admired for candidly expressing his doubts about string theory’s aspiration to represent all forces and matter in one coherent system. “I think Freeman wishes the string theorists well,” Avishai Margalit, the philosopher, says. “I don’t think he wishes them luck. He’s interested in diversity, and that’s his worldview. To me he is a towering figure although he is tiny — almost a saintly model of how to get old. The main thing he retains is playfulness. Einstein had it. Playfulness and curiosity. He also stands for this unique trait, which is wisdom. Brightness here is common. He is wise. He integrated, not in a theory, but in his life, all his dreams of things.”

IMME DYSON REPORTS that her husband “recently stopped climbing trees.” Dyson himself says he’s resigned to never finishing “Anna Karenina.” Otherwise he still lives his days at mortality-ignoring cadence, aided by NoDoz, a habit he first acquired during his R.A.F. days. He travels widely, giving talks at churches and colleges, reminding people how dangerous nuclear weapons are. (“I think people got used to them and think if you leave them alone, they won’t do you any harm,” he says. “I always am scared. I think everybody ought to be.”) He has visited both the Galápagos Islands and the campus of Google and attended “Doctor Atomic,” the John Adams opera about Oppenheimer, which disappointed him. More fulfilling was the board meeting of a foundation promoting solar energy in China. Another winter day found him answering questions from physics majors at a Christian college in Oklahoma. (“Scientists should understand the human anguish of religious people,” he says.)

Lately Dyson has been lamenting that he and Imme “don’t see so much of each other. We’re always rushing around.” But one evening last month they sat down in a living room filled with Imme’s running trophies and photographs of their children to watch “An Inconvenient Truth” again. There was a print of Einstein above the television. And then there was Al Gore below him, telling of the late Roger Revelle, a Harvard scientist who first alerted the undergraduate Gore to how severe the climate’s problems would become. Gore warned of the melting snows of Kilimanjaro, the vanishing glaciers of Peru and “off the charts” carbon levels in the air. “The so-called skeptics” say this “seems perfectly O.K.,” Gore said, and Imme looked at her husband. She is even slighter than he is, a pretty wood sprite in running shoes. “How far do you allow the oceans to rise before you say, This is no good?” she asked Dyson.

“When I see clear evidence of harm,” he said.

“Then it’s too late,” she replied. “Shouldn’t we not add to what nature’s doing?”

“The costs of what Gore tells us to do would be extremely large,” Dyson said. “By restricting CO2 you make life more expensive and hurt the poor. I’m concerned about the Chinese.”

“They’re the biggest polluters,” Imme replied.

“They’re also changing their standard of living the most, going from poor to middle class. To me that’s very precious.”

The film continued with Gore predicting violent hurricanes, typhoons and tornados. “How in God’s name could that happen here?” Gore said, talking about Hurricane Katrina. “Nature’s been going crazy.”

“That is of course just nonsense,” Dyson said calmly. “With Katrina, all the damage was due to the fact that nobody had taken the trouble to build adequate dikes. To point to Katrina and make any clear connection to global warming is very misleading.”

Now came Arctic scenes, with Gore telling of disappearing ice, drunken trees and drowning polar bears. “Most of the time in history the Arctic has been free of ice,” Dyson said. “A year ago when we went to Greenland where warming is the strongest, the people loved it.”

“They were so proud,” Imme agreed. “They could grow their own cabbage.”

The film ended. “I think Gore does a brilliant job,” Dyson said. “For most people I’d think this would be quite effective. But I knew Roger Revelle. He was definitely a skeptic. He’s not alive to defend himself.”

“All my friends say how smart and farsighted Al Gore is,” she said.

“He certainly is a good preacher,” Dyson replied. “Forty years ago it was fashionable to worry about the coming ice age. Better to attack the real problems like the extinction of species and overfishing. There are so many practical measures we could take.”

“I’m still perfectly happy if you buy me a Prius!” Imme said.

“It’s toys for the rich,” her husband smiled, and then they were arguing about windmills.

Nicholas Dawidoff, a contributing writer for the magazine, is the author of four books, most recently “The Crowd Sounds Happy.”

|

|

|

|

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4289

Reputation: 8.16

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:The Flipping Point

« Reply #216 on: 2009-03-30 03:59:55 » |

|

Freeman Dyson ...

[Hermit] A contrarian from birth. Definitely an elder scientist way out of field - so probably wrong on many if not most issues. Likely correct on some things and wrong on others, not necessarily for the right - or wrong - reasons.

[Hermit] I agree with him on some things, for example, we will need to use every possible energy source in the near future as oil becomes much more expensive to obtain, including coal, though I disagree on how; and he is completely wrong about the cost of making a world which can sustain the current population until we can reduce it to sane levels - while reducing our per capita environmental footprint.

[Iolo Morganwg] Dear Hermit and others, I think that it is time for my contributions to this thread to cease.

[Hermit] I suspect that while neither of us knows enough to close the topic conclusively, arguing the consensus position, I have the advantage of more and better sources (though often less accessible and readable I fear). While I will continue to urge you to reconsider your position (and perhaps articulate it better), and guarantee a robust response whenever I can find the time, I don't think merely withholding dissent is an appropriate approach.

[Iolo Morganwg] I do acknowledge that human emissions are perturbing the natural cycle,

[Hermit] Sensible.

[Iolo Morganwg] but I am failing miserably to get the nuance of my position across successfully.

[Hermit] Nods. It seems likely.

[Iolo Morganwg] We humans are doing an experiment on the atmosphere/surface system and we do not have a control planet to compare our results with. That makes it a bit tricky, but we have to manage somehow to try to understand what is happening.

[Hermit] it is quite easy, if physics keep working the way they used to, then increasing greenhouse gases will result in a hotter planet. This probably won't be good for humans. Is this caused by us? The consensus says yes. I say probably, but emphasise that it doesn't matter how it is caused, we urgently need to try to stop peeing on our planet, address aggravating conditions and seek ways to attempt to ameliorate the consequences of change, no matter what is driving the processes.

[Iolo Morganwg] This has been my purpose for participation.

[Hermit] :-)

[Iolo Morganwg] However, with this recent round of posts I get the distinct impression that my contributions are neither valued or respected.

[Hermit] Not at all. I admire your persistence, ability to dig out arguments that require thought to deal with and willingness to be wrong and cede positions - as well as your logical approach and generally competent argument.

[Iolo Morganwg] I can only contribute to discussions as far as my understanding extends, and whilst perhaps hopefully limited, I do not think that such a limitation of knowledge needs to be likened to flat-earthers or other such tin hat wearers.

[Hermit] I'm afraid that I can quote multiple "respected sources" drawing exactly this parallel. My interpretation is that it relates directly to the degree of frustration raised in experts by people who don't have the competence to evaluate the facts or the analysis, but who disagree with the consensus position, apparently for reasons having nothing to do with the conclusions, and who seem to seek desperately for supporting data or theories to sustain their beliefs - and generally just don't get it. Neither of us belonging in either group, my quoting this was not intended as a jibe, but rather as a simple reminder of the reality which exists behind the limited discussions being held here. For the reasons already provided, the "real" experts are no longer engaging in conversations such as these, so perhaps we do serve some small purpose.

[Hermit] Don't forget to have fun :-)

[Iolo Morganwg] Indeed. I seem to have forgotten this recently. Thanks for the reminder.

[Hermit] It is important. Bows.

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

the.bricoleur

Adept

Posts: 341

Reputation: 7.35

Rate the.bricoleur

making sense of change

|

|

Re:The Flipping Point

« Reply #217 on: 2009-04-02 15:56:45 » |

|

I would like to thank you all for the feedback re my contributions. The feedback holds a great deal of value to me.

I do not think that locking this thread is the direction to take as it would not allow any new information to be shared.

On that note, if I come across any information that I think would shed light on the topic, I will share it.

To Hermit: I thank you for being a gentleman, but one with a firm hand.

Kind regards,

-iolo

|

|

|

|

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4289

Reputation: 8.16

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:The Flipping Point

« Reply #218 on: 2009-04-03 22:49:05 » |

|

Study: Arctic sea ice melting faster than expected

[ Hermit : Note that it is the air temperature which is 5C above that anticipated, not the sea temperature, and that a reduction of 30% in sea ice extent is probably significant. ]

Source: Associated Press

Authors: Randolph E. Schmid (AP Science Writer)

Dated: 2009-04-03

Arctic sea ice is melting so fast most of it could be gone in 30 years. A new analysis of changing conditions in the region, using complex computer models of weather and climate, says conditions that had been forecast by the end of the century could occur much sooner.