Author

Author

|

Topic: Sorry. Most of What You Think You Know is Wrong. WW II redux. (Read 4538 times) |

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4289

Reputation: 8.16

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Sorry. Most of What You Think You Know is Wrong. WW II redux.

« on: 2006-05-17 13:37:13 » |

|

December 7, 1941: A Setup from the Beginning

[Hermit: An old article, but perhaps worthy of wider dissemination. This article presents a compelling reason why secrecy is a bad idea - if only because it prevents us from learning from the mistakes of the past.]

Source: The Independence Institute

Authors: Robert B. Stinnett

Dated: 2000-12-07

As Americans honor those 2403 men, women, and children killed—and 1178 wounded—in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on December 7, 1941, recently released government documents concerning that “surprise” raid compel us to revisit some troubling questions.

At issue is American foreknowledge of Japanese military plans to attack Hawaii by a submarine and carrier force 59 years ago. There are two questions at the top of the foreknowledge list: (1) whether President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his top military chieftains provoked Japan into an “overt act of war” directed at Hawaii, and (2) whether Japan’s military plans were obtained in advance by the United States but concealed from the Hawaiian military commanders, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel and Lieutenant General Walter Short so they would not interfere with the overt act.

The latter question was answered in the affirmative on October 30, 2000, when President Bill Clinton signed into law, with the support of a bipartisan Congress, the National Defense Authorization Act. Amidst its omnibus provisions, the Act reverses the findings of nine previous Pearl Harbor investigations and finds that both Kimmel and Short were denied crucial military intelligence that tracked the Japanese forces toward Hawaii and obtained by the Roosevelt Administration in the weeks before the attack.

Congress was specific in its finding against the 1941 White House: Kimmel and Short were cut off from the intelligence pipeline that located Japanese forces advancing on Hawaii. Then, after the successful Japanese raid, both commanders were relieved of their commands, blamed for failing to ward off the attack, and demoted in rank.

President Clinton must now decide whether to grant the request by Congress to restore the commanders to their 1941 ranks. Regardless of what the Commander-in-Chief does in the remaining months of his term, these congressional findings should be widely seen as an exoneration of 59 years of blame assigned to Kimmel and Short.

But one important question remains: Does the blame for the Pearl Harbor disaster revert to President Roosevelt?

A major motion picture based on the attack is currently under production by Walt Disney Studios and scheduled for release in May 2001. The producer, Jerry Bruckheimer, refuses to include America’s foreknowledge in the script. When Bruckheimer commented on FDR’s foreknowledge in an interview published earlier this year, he said “That’s all b___s___.

Yet, Roosevelt believed that provoking Japan into an attack on Hawaii was the only option he had in 1941 to overcome the powerful America First non-interventionist movement led by aviation hero Charles Lindbergh. These anti-war views were shared by 80 percent of the American public from 1940 to 1941. Though Germany had conquered most of Europe, and her U-Boats were sinking American ships in the Atlantic Ocean—including warships—Americans wanted nothing to do with “Europe’s War.”

However, Germany made a strategic error. She, along with her Axis partner, Italy, signed the mutual assistance treaty with Japan, the Tripartite Pact, on September 27, 1940. Ten days later, Lieutenant Commander Arthur McCollum, a U.S. Naval officer in the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), saw an opportunity to counter the U.S. isolationist movement by provoking Japan into a state of war with the U.S., triggering the mutual assistance provisions of the Tripartite Pact, and bringing America into World War II.

Memorialized in McCollum’s secret memo dated October 7, 1940, and recently obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, the ONI proposal called for eight provocations aimed at Japan. Its centerpiece was keeping the might of the U.S. Fleet based in the Territory of Hawaii as a lure for a Japanese attack.

President Roosevelt acted swiftly. The very next day, October 8, 1940, the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet, Admiral James O. Richardson, was summoned to the Oval Office and told of the provocative plan by the President. In a heated argument with FDR, the admiral objected to placing his sailors and ships in harm’s way. Richardson was then fired and in his place FDR selected an obscure naval officer, Rear Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, to command the fleet in Hawaii. Kimmel was promoted to a four-star admiral and took command on February 1, 1941. In a related appointment, Walter Short was promoted from Major General to a three-star Lieutenant General and given command of U.S. Army troops in Hawaii.

Throughout 1941, FDR implemented the remaining seven provocations. He then gauged Japanese reaction through intercepted and decoded communications intelligence originated by Japan’s diplomatic and military leaders.

The island nation’s militarists used the provocations to seize control of Japan and organized their military forces for war against the U.S., Great Britain, and the Netherlands. The centerpiece—the Pearl Harbor attack—was leaked to the U.S. in January 1941. During the next 11 months, the White House followed the Japanese war plans through the intercepted and decoded diplomatic and military communications intelligence.

Japanese leaders failed in basic security precautions. At least 1,000 Japanese military and diplomatic radio messages per day were intercepted by monitoring stations operated by the U.S. and her Allies, and the message contents were summarized for the White House. The intercept summaries were clear: Pearl Harbor would be attacked on December 7, 1941, by Japanese forces advancing through the Central and North Pacific Oceans. On November 27 and 28, 1941, Admiral Kimmel and General Short were ordered to remain in a defensive posture for “the United States desires that Japan commit the first overt act.” The order came directly from President Roosevelt.

As I explained to a policy forum audience at The Independent Institute in Oakland, California, which was videotaped and telecast nationwide over the Fourth of July holiday earlier this year, my research of U.S. naval records shows that not only were Kimmel and Short cut off from the Japanese communications intelligence pipeline, so were the American people. It is a coverup that has lasted for nearly 59 years.

Immediately after December 7, 1941, military communications documents that disclose American foreknowledge of the Pearl Harbor disaster were locked in U.S. Navy vaults away from the prying eyes of congressional investigators, historians, and authors. Though the Freedom of Information Act freed the foreknowledge documents from the secretive vaults to the sunlight of the National Archives in 1995, a cottage industry continues to cover up America’s foreknowledge of Pearl Harbor.

Robert B. Stinnett is a Research Fellow at The Independent Institute in Oakland, Calif. and the author of Day of Deceit: The Truth about FDR and Pearl Harbor (Free Press). This article is adapted from Robert B. Stinnett's presentation before the Independent Policy Forum, “Pearl Harbor: Official Lies in an American War Tragedy?”, held May 24, 2000.

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4289

Reputation: 8.16

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:Sorry. Most of What You Think You Know is Wrong. WW II redux.

« Reply #1 on: 2006-07-31 13:15:07 » |

|

Remembering Hiroshima

Source: Antiwar.com

Authors: David R. Henderson [Research fellow with the Hoover Institution, Associate Professor of Economics in the Graduate School of Business and Public Policy at the Naval Postgraduate School]

Dated: 2006-07-31

Sometimes, something happens that is so awful that we find ourselves rationalizing it, talking as if it had to happen, to make ourselves feel better about the horrible event. For many people, I believe, President Truman's dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, and on Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945, were two such events. After all, if the leader of arguably the freest country in the world decided to drop those bombs, he had to have a good reason, didn't he? I grew up in Canada thinking that, horrible as it was, dropping the atomic bombs on those two cities was justified. Although I never believed that the people those bombs killed were mainly guilty people, I could at least tell myself that many more innocent people, including American military conscripts, would have been killed had the bombs not been dropped. But then I started to investigate. On the basis of that investigation, I have concluded that dropping the bomb was not necessary and caused, on net, tens of thousands, and possibly more than a hundred thousand, more deaths than were necessary.

What I write below will not come as a surprise to those who are particularly well-informed about the issue: the Gar Alperovitzes, Barton Bernsteins, Dennis Wainstocks, and Ralph Raicos of the world. But it did come as a surprise to me and will surprise, I believe, many of the people reading this article. There were four surprises: (1) how Truman himself couldn't seem to keep his story straight about why he dropped the bomb and even whom he dropped the first one on; (2) how strong the opinion was among the informed, including many military and political leaders, against dropping the bomb; (3) how strong a case can be made that the Japanese government was about to surrender and that the U.S. insistence on unconditional surrender had already delayed their surrender for months; and (4) how the proponents of dropping the bomb systematically and successfully convinced Americans that dropping the bomb saved many American lives. On the third issue, in particular, I highlight a May 1945 memo to President Truman from former President Herbert Hoover, the person who founded the Hoover Institution, at which I am proudly, given his views on this, a research fellow.

Truman's Story

Start with Truman. In a long, rambling speech to the American people on radio on Aug. 9, three days after the Enola Gay dropped the bomb on Hiroshima and hours after Bockscar dropped it on Nagasaki, Truman announced, "The world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base. That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians." Actually, of course, it was not a military base, but a city, a fact that Truman must have known before he made the decision. And if he didn't know it, then how horrible is that? Someone who wants to drop a nuclear bomb on a target should surely do due diligence to find out what the target is. That seems like a minimal requirement.

Nevertheless, whatever he knew or didn't know, Truman clearly stated above that he wanted to avoid killing civilians. But did he? In response to a clergyman who criticized his decision, Truman wrote:

"Nobody is more disturbed over the use of Atomic bombs than I am but I was greatly disturbed over the unwarranted attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor and their murder of our prisoners of war. The only language they seem to understand is the one we have been using to bombard them. When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him as a beast. It is most regrettable but nevertheless true."[1]

Here, Truman sounds more like a man bent on vengeance than a man worrying about needless loss of civilian lives.

And how regrettable was it to Truman? He later wrote, "I telephoned Byrnes [his secretary of state] aboard ship to give him the news and then said to the group of sailors around me, 'This is the greatest thing in history.'" In response to a story in the Aug. 7 Oregon Journal headlined "Truman, Jubilant Over New Bomb, Nears U.S. Port," Lew Wallace, a Democratic politician from Portland, Oregon, telegrammed Truman:

"We on the Pacific Coast and all Americans know that no president of the United States could ever be jubilant over any device that would kill innocent human beings. Please make it clear that it is not destruction but the end of destruction that is the cause of jubilation."

Truman replied on Aug. 9:

"I appreciated your telegram very much but I think if you will read the paper again you will find that the good feeling on my part was over the fact Russia had entered into the war with Japan and not because we had invented a new engine of destruction."

There are two small problems with Truman's version. First, Truman wasn't jubilant about Russia's entry. Second and more important, the timing doesn't work. When Truman claimed to have been jubilant about Russia's entry into the war, Russia hadn't yet entered. Russia entered the war on Aug. 8.

The Opposition to Dropping the Bomb

Start with this shocking quote – shocking because of the source:

"Careful scholarly treatment of the records and manuscripts opened over the past few years has greatly enhanced our understanding of why the Truman administration used atomic weapons against Japan. Experts continue to disagree on some issues, but critical questions have been answered. The consensus among scholars is that the bomb was not needed to avoid an invasion of Japan and to end the war within a relatively short time. It is clear that alternatives to the bomb existed and that Truman and his advisers knew it."

The author of the above quote: J. Samuel Walker, chief historian of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.[2]

But what about the idea that the Japanese would fiercely resist an invasion of their main islands? It is one of those myths that have come about with few apparent facts to support it. The various military men who were close to the action were quite confident that the Japanese had been so thoroughly bombed and their infrastructure so thoroughly destroyed that there was no need for the atom bomb. The literature is rife with quotes to that effect.

Take, for example, Curtis E. LeMay, the Air Force general who led B-29 bombing of Japanese cities late in the war. LeMay once said, "There are no innocent civilians, so it doesn't bother me so much to be killing innocent bystanders." And he was as good as his word: in one night of fire-bombing Tokyo, he and his men killed 100,000 civilians. So we can be confident that any doubts he had about dropping the atom bomb would not be based on concern for Japanese civilians. But consider the following dialogue between LeMay and the press.

"LeMay: The war would have been over in two weeks without the Russians entering and without the atomic bomb.

"The Press: You mean that, sir? Without the Russians and the atomic bomb?

"LeMay: Yes, with the B-29…

"The Press: General, why use the atomic bomb? Why did we use it then?

"LeMay: Well, the other people were not convinced…

"The Press: Had they not surrendered because of the atomic bomb?

"LeMay: The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all."[3]

Nor was LeMay alone. Other Air Force officers, all documented in Alperovitz, had reached similar conclusions. And Navy admirals and Army generals also believed that dropping the bomb was a bad idea. Fleet Admiral Leahy, for instance, the chief of staff to the president and a friend of Truman's, thought the atom bomb unnecessary. Furthermore, he wrote, "in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages."[4] Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet and chief of Naval Operations, thought the war could be ended well before a planned November 1945 naval invasion. And in a public speech on Oct. 5, 1945, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, said, "The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace before the atomic age was announced to the world with the destruction of Hiroshima and before the Russian entry into the war."[5]

Many Army leaders had similar views. Author Norman Cousins writes of Gen. Douglas MacArthur:

"[H]e saw no military justification for the dropping of the bomb. The war might have ended weeks earlier, he said, if the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the emperor."[6]

Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the Allied Forces in Europe, was also against the bomb. Eisenhower biographer Stephen Ambrose writes:

"There was one additional matter on which Eisenhower gave Truman advice that was ignored. It concerned the use of the atomic bomb. Eisenhower first heard of the bomb during the Potsdam Conference; from that moment on, until his death, it occupied, along with the Russians, a central position in his thinking. …

"When [Secretary of War] Stimson said the United States proposed to use the bomb against Japan, Eisenhower voiced '… grave misgivings….' Three days later, on July 20, Eisenhower flew to Berlin, where he met with Truman and his principal advisors. Again Eisenhower recommended against using the bomb, and again was ignored."[7]

These are a few of the many quotes in Alperovitz from military leaders who thought the bomb's use on Japan unnecessary and/or immoral.

Much of what I've written in this section is subject to the criticism that, of course, these leaders wanted to distance themselves from a bad decision, but that that doesn't necessarily mean they were opposed at the time or, more important, expressed their opposition at the time. In short, all these people could be lying. However, Alperovitz gives enough evidence to conclude, at the very least, that not all of them were lying. Some of the documents are memos written well before Aug. 6, 1945.

The Weak Case for Using the Bomb

Even though it's clear that not all of these opponents lied after the fact about their opposition, assume for a minute that they had. There still would be no good case for using the bomb. Roosevelt and Truman had made clear that they were seeking "unconditional surrender" from Japan. But Truman adamantly refused to clarify what "unconditional surrender" meant.

One of the key issues in the U.S. government's call for the Japanese government's unconditional surrender was whether the Japanese would be able to keep their emperor. Former President Herbert Hoover was very active in trying to end the war with Japan. On May 16, 1945, he sent a memo to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, who had been Hoover's secretary of state, outlining his views on the war. On May 28, he met with President Truman and discussed how to end the war. At Truman's request, Hoover wrote a memo in which he urged that the terms of Japan's surrender be clarified. He emphasized that the U.S. government should make clear to Japan's government that "the Allies have no desire to destroy either the Japanese people or their government, or to interference [sic] in the Japanese way of life."[8] Truman gave the Hoover memo to Stimson and undersecretary of state Joseph Grew for comments. On June 14, fully seven weeks before the bomb was dropped, Stimson's staff gave its assessment:

"The proposal of a public declaration of war aims, in effect giving definition to 'unconditional surrender,' has definite merit if it is carefully handled."[9]

There is ample evidence that the Japanese government was willing to surrender months before Aug. 6 if only it could keep its emperor. Much of this evidence is given in Alperovitz's book and much in Dennis D. Wainstock, The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1996). Wainstock (pp. 22-23) tells of many attempts by the Japanese to clarify the terms and to make clear their willingness to surrender if they could only keep their emperor untouched. For example, on April 7, 1945, acting Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru asked Swedish Ambassador Widon Bagge in Tokyo "to ascertain what peace terms the United States and Britain had in mind." Shigemitsu emphasized that "the Emperor must not be touched." Bagge passed the message on to the U.S. government, but Secretary of State Edward Stettinius told the U.S. ambassador in Sweden to "show no interest or take any initiative in pursuit of this matter."[10]

So the Japanese government tried another route. On May 7, 1945, Masutard Inoue, counselor of the Japanese legation in Portugal, approached an agent of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Inoue asked the agent to contact the U.S. embassy and "find out exactly what they plan to do in the Far East." He expressed his fear that Japan would be smashed, and he emphasized, "there can be no unconditional surrender." The agent passed the message on, but nothing came of it.

Three times is a charm, goes the saying. But not for the hapless Japanese. On May 10, 1945, Gen. Onodera, Japan's military representative in Sweden, tried to get a member of Sweden's royal family to approach the Allies for a settlement. He emphasized also that Japan's government would not accept unconditional surrender and must be allowed to "save face." The U.S. government urged Sweden's government to let the matter drop.

But if you can't at first surrender, try, try again. On July 12, with almost four weeks to go before the horrible blast, Kojiro Kitamura, a representative of the Yokohama Specie Bank in Switzerland, told Per Jacobson, a Swedish adviser to the Bank for International Settlements, that he wanted to contact U.S. representatives and that the only condition Japan insisted on was that it keep its emperor. "He was acting with the consent of Shunichi Kase, the Japanese minister to Switzerland, and General Kiyotomi Okamoto, chief of Japanese European intelligence, and they were in direct contact with Tokyo."[11] On July 14, Jacobson met in Wiesbaden, Germany with OSS representative Allen Dulles (later head of the CIA) and relayed the message that Japan's main demand was "retention of the Emperor."[i] Dulles passed the information to Stimson, but Stimson refused to act on it.

Interestingly, Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy drafted a proposed surrender demand for the Committee of Three (Grew, Stimson, and Navy Secretary James Forrestal.) Their draft was part of Article 12 of the Potsdam Declaration, in which the Allies specified the conditions for Japan's surrender. Under their wording, Japan's government would have been allowed to keep its emperor as part of a "constitutional monarchy." Truman, though, who was influenced by his newly appointed Secretary of State James Byrnes on the ship over to the Potsdam Conference, changed the language of the surrender demand to drop the reference to keeping the emperor.

The bitter irony, of course, is that Truman ultimately allowed Japan to keep its emperor. Had this condition been dropped earlier, there would have been no need for the atom bomb. Rather than let Japan's government "save face," Truman destroyed almost 200,000 faces.

Why did this happen? Why did Truman persist in refusing to clarify what unconditional surrender meant? Alperovitz speculates, with evidence that some will find convincing and others won't, that the reason was to send a signal to Joseph Stalin that the U.S. government was willing to use some pretty vicious methods to dominate in the postwar world. My own view is that Truman and Byrnes wanted vengeance, plain and simple, and cared little about the loss of innocent lives. Let's face it: dropping an atom bomb on two non-militarily strategic cities was not different in principle from fire-bombing Tokyo or Dresden.

Rewriting History

Why is it that when people talk Hiroshima and Nagasaki today, the standard response from defenders of the decision is that dropping these bombs saved hundreds of thousands and, in some versions, millions, of American lives? The reason is that some of those who had most favored using the bomb, or who had gone along with the decision, participated in a highly successful attempt to craft history.

Even Jimmy Byrnes, the aforementioned secretary of state and one of the strongest advocates of using the bomb, claimed in his memoirs only the following: [i]"Certainly, by bringing the war to an end, the atomic bomb saved the lives of thousands of American boys."[i][12] But, by 1991, President George H.W. Bush was claiming that the decision to use the bomb [i]"spared millions [emphasis mine] of American lives." What happened that made Americans take this kind of claim seriously?

Within a year of the war's end, articles started appearing in the U.S. that questioned the need for dropping the bomb or that simply laid out, in very human terms, its devastating consequences. In a June 1946 article in Saturday Review, for example, editor Norman Cousins and co-author Thomas K. Finletter, a former assistant secretary of state and, later, secretary of the Air Force, raised the question of why the bomb was dropped. They speculated:

"Can it be that we were more anxious to prevent Russia from establishing a claim for full participation in the occupation against Japan than we were to think through the implications of unleashing atomic warfare?"[13]

Other popular articles followed. On Aug. 19, 1946, the New York Times reported that Albert Einstein deplored the use of the bomb and speculated that it was a way of getting to Japan before the Russians did. On Aug. 31, The New Yorker devoted its entire issue to John Hersey's Hiroshima, which laid out the horrible human tragedy. It didn't help the proponents' case that in July 1946, the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey's book, Japan's Struggle to End the War, was published. It concluded that Japan would have surrendered without the bomb, without the Soviet declaration of war, and without even a U.S. invasion.

In the minds of proponents of using the bomb, something had to be done. James B. Conant, for example, Harvard University's president and one of the leading advocates of the bomb's use, concluded that an article was needed to counter this growing wave of criticism. The best candidate for the job, he concluded, was Henry Stimson. Stimson had been in both Hoover's and Truman's administrations and was highly respected. Conant suggested to Harvey Bundy, who had been one of the main overseers of the Manhattan Project that had developed the bomb, that he draft an article for Stimson's signature. The actual author of the article was Harvey Bundy's young son, McGeorge Bundy, who later figured so prominently as a Kennedy administration official in favor of the Vietnam war. Alperovitz tells the story so well (pp. 448-497) that I can't do justice to it here. But here are two highlights of the points the article was to make:- That if the bomb hadn't been used, "thousands and perhaps hundreds of thousands of American soldiers might be [sic] killed or permanently injured."

- That "nobody in authority in Potsdam was satisfied that the Japanese would surrender on terms acceptable to the Allies without further bitter fighting."

As we have seen, both of these claims were false. Conant, moreover, successfully persuaded Bundy to drop mention of the issue of "unconditional surrender." This is like asking a sports writer writing about football player Terrell Owens' conflicts to drop any mention of his criticism of Philadelphia Eagles' quarterback Donovan McNabb. Why confuse readers with the facts?

The final draft was published in the February 1947 Harper's and widely reprinted. It silenced all but the most-independent critics. If you find yourself making claims about all the American lives saved and about the Japanese intransigence in the face of certain defeat, as I used to, you can probably thank McGeorge Bundy, Henry Stimson, and James B. Conant. But if you want the facts, read pp. 448-497 of Alperovitz.

Notes

1. Quoted in Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995, p. 563.

2. J. Samuel Walker, "The Decision to Use the Bomb: A Historiographical Update," Diplomatic History, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Winter 1990), pp. 97-114. (Quoted in Alperovitz, 1995.)

3. Quoted in Alperovitz, 1995, p. 336.

4. William D. Leahy, I Was There, pg. 441, quoted at http://www.doug-long.com/leahy.htm.

5. Alperowitz, p. 329.

6. Cousins, Pathology of Power, 1987, p. 71, quoted in Alperovitz, 1995.

7. Stephen E. Ambrose, Eisenhower, Vol I: Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect, 1890-1952 (New York, 1983), pp. 425-426, quoted in Alperovitz, p. 358.

8. Quoted in Alperovitz, p. 44.

9. Quoted in Alperovitz, p. 44.

10. Quoted in Wainstock, p. 22.

11. Wainstock, p. 23.

12. James F. Byrnes, Speaking Frankly, New York: Harper and Brothers, 1947, p. 264.

13. Quoted in Alperovitz, p. 443.

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4289

Reputation: 8.16

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:Sorry. Most of What You Think You Know is Wrong. WW II/Vietnam redux.

« Reply #2 on: 2006-08-08 05:37:05 » |

|

Vietnam: The War Crimes Files

[Hermit: I have just finished reading a reprise of one of Chomsky's brilliantly written analysis of war crimes in Iraq, which makes a strong case that Our Inglorious Leadertm is in fact quite probably exposed to the possibility of the death sentence, under American law, for the horrors we are involved in in Iraq (and, I suggest in Afghanistan as well, not to mention his support for our genocidal friends, the Israelis) - if anyone could be bothered about prosecuting him and his cronies. This article helped to put the lack of interest into what may be seen as "an appropriate perspective" - as merely our latest involvement in a glorious tradition of ignoring war crimes when committed by "our boys" and their leaders (while of course, quite happy to execute "their" leaders on rumor, hearsay and blatant fabrication.]

Source: The Los Angeles Times

Authors: Nick Turse, Deborah Nelson, Janet Lundblad

Dated: 2006-08-06

The men of B Company were in a dangerous state of mind. They had lost five men in a firefight the day before. The morning of Feb. 8, 1968, brought unwelcome orders to resume their sweep of the countryside, a green patchwork of rice paddies along Vietnam's central coast.

They met no resistance as they entered a nondescript settlement in Quang Nam province. So Jamie Henry, a 20-year-old medic, set his rifle down in a hut, unfastened his bandoliers and lighted a cigarette.

Just then, the voice of a lieutenant crackled across the radio. He reported that he had rounded up 19 civilians, and wanted to know what to do with them. Henry later recalled the company commander's response:

Kill anything that moves.

Henry stepped outside the hut and saw a small crowd of women and children. Then the shooting began.

Moments later, the 19 villagers lay dead or dying.

Back home in California, Henry published an account of the slaughter and held a news conference to air his allegations. Yet he and other Vietnam veterans who spoke out about war crimes were branded traitors and fabricators. No one was ever prosecuted for the massacre.

Now, nearly 40 years later, declassified Army files show that Henry was telling the truth - about the Feb. 8 killings and a series of other atrocities by the men of B Company.

The files are part of a once-secret archive, assembled by a Pentagon task force in the early 1970s, that shows that confirmed atrocities by U.S. forces in Vietnam were more extensive than was previously known.

The documents detail 320 alleged incidents that were substantiated by Army investigators - not including the most notorious U.S. atrocity, the 1968 My Lai massacre.

Though not a complete accounting of Vietnam war crimes, the archive is the largest such collection to surface to date. About 9,000 pages, it includes investigative files, sworn statements by witnesses and status reports for top military brass.

The records describe recurrent attacks on ordinary Vietnamese - families in their homes, farmers in rice paddies, teenagers out fishing. Hundreds of soldiers, in interviews with investigators and letters to commanders, described a violent minority who murdered, raped and tortured with impunity.

Abuses were not confined to a few rogue units, a Times review of the files found. They were uncovered in every Army division that operated in Vietnam.

Retired Brig. Gen. John H. Johns, a Vietnam veteran who served on the task force, says he once supported keeping the records secret but now believes they deserve wide attention in light of alleged attacks on civilians and abuse of prisoners in Iraq.

"We can't change current practices unless we acknowledge the past," says Johns, 78.

Among the substantiated cases in the archive:

Seven massacres from 1967 through 1971 in which at least 137 civilians died.

Seventy-eight other attacks on noncombatants in which at least 57 were killed, 56 wounded and 15 sexually assaulted.

One hundred forty-one instances in which U.S. soldiers tortured civilian detainees or prisoners of war with fists, sticks, bats, water or electric shock.

Investigators determined that evidence against 203 soldiers accused of harming Vietnamese civilians or prisoners was strong enough to warrant formal charges. These "founded" cases were referred to the soldiers' superiors for action.

Ultimately, 57 of them were court-martialed and just 23 convicted, the records show.

Fourteen received prison sentences ranging from six months to 20 years, but most won significant reductions on appeal. The stiffest sentence went to a military intelligence interrogator convicted of committing indecent acts on a 13-year-old girl in an interrogation hut in 1967.

He served seven months of a 20-year term, the records show.

Many substantiated cases were closed with a letter of reprimand, a fine or, in more than half the cases, no action at all.

There was little interest in prosecuting Vietnam war crimes, says Steven Chucala, who in the early 1970s was legal advisor to the commanding officer of the Army's Criminal Investigation Division. He says he disagreed with the attitude but understood it.

"Everyone wanted Vietnam to go away," says Chucala, now a civilian attorney for the Army at Ft. Belvoir in Virginia.

In many cases, suspects had left the service. The Army did not attempt to pursue them, despite a written opinion in 1969 by Robert E. Jordan III, then the Army's general counsel, that ex-soldiers could be prosecuted through courts-martial, military commissions or tribunals.

"I don't remember why it didn't go anywhere," says Jordan, now a lawyer in Washington.

Top Army brass should have demanded a tougher response, says retired Lt. Gen. Robert G. Gard, the highest-ranking member of the Pentagon task force in the early 1970s.

"We could have court-martialed them but didn't," Gard says of soldiers accused of war crimes. "The whole thing is terribly disturbing."

Early-Warning System

In March 1968, members of the 23rd Infantry Division slaughtered about 500 Vietnamese civilians in the hamlet of My Lai. Reporter Seymour Hersh exposed the massacre the following year.

By then, Gen. William C. Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam at the time of My Lai, had become Army chief of staff. A task force was assembled from members of his staff to monitor war crimes allegations and serve as an early-warning system.

Over the next few years, members of the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group reviewed Army investigations and wrote reports and summaries for military brass and the White House.

The records were declassified in 1994, after 20 years as required by law, and moved to the National Archives in College Park, Md., where they went largely unnoticed.

The Times examined most of the files and obtained copies of about 3,000 pages - about a third of the total - before government officials removed them from the public shelves, saying they contained personal information that was exempt from the Freedom of Information Act.

In addition to the 320 substantiated incidents, the records contain material related to more than 500 alleged atrocities that Army investigators could not prove or that they discounted.

Johns says many war crimes did not make it into the archive. Some were prosecuted without being identified as war crimes, as required by military regulations. Others were never reported.

In a letter to Westmoreland in 1970, an anonymous sergeant described widespread, unreported killings of civilians by members of the 9th Infantry Division in the Mekong Delta - and blamed pressure from superiors to generate high body counts.

"A batalion [sic] would kill maybe 15 to 20 [civilians] a day. With 4 batalions in the brigade that would be maybe 40 to 50 a day or 1200 to 1500 a month, easy," the unnamed sergeant wrote. "If I am only 10% right, and believe me it's lots more, then I am trying to tell you about 120-150 murders, or a My Lay [sic] each month for over a year."

A high-level Army review of the letter cited its "forcefulness," "sincerity" and "inescapable logic," and urged then-Secretary of the Army Stanley R. Resor to make sure the push for verifiable body counts did not "encourage the human tendency to inflate the count by violating established rules of engagement."

Investigators tried to find the letter writer and "prevent his complaints from reaching" then-Rep. Ronald V. Dellums (D-Oakland), according to an August 1971 memo to Westmoreland.

The records do not say whether the writer was located, and there is no evidence in the files that his complaint was investigated further.

Pvt. Henry

James D. "Jamie" Henry was 19 in March 1967, when the Army shaved his hippie locks and packed him off to boot camp.

He had been living with his mother in Sonoma County, working as hospital aide and moonlighting as a flower child in Haight-Ashbury, when he received a letter from his draft board. As thousands of hippies poured into San Francisco for the upcoming "Summer of Love," Henry headed for Ft. Polk, La.

Soon he was on his way to Vietnam, part of a 100,000-man influx that brought U.S. troop strength to 485,000 by the end of 1967. They entered a conflict growing ever bloodier for Americans - 9,378 U.S. troops would die in combat in 1967, 87% more than the year before.

Henry was a medic with B Company of the 1st Battalion, 35th Infantry, 4th Infantry Division. He described his experiences in a sworn statement to Army investigators several years later and in recent interviews with The Times.

In the fall of 1967, he was on his first patrol, marching along the edge of a rice paddy in Quang Nam province, when the soldiers encountered a teenage girl.

"The guy in the lead immediately stops her and puts his hand down her pants," Henry said. "I just thought, 'My God, what's going on?' "

A day or two later, he saw soldiers senselessly stabbing a pig.

"I talked to them about it, and they told me if I wanted to live very long, I should shut my mouth," he told Army investigators.

Henry may have kept his mouth shut, but he kept his eyes and ears open.

On Oct. 8, 1967, after a firefight near Chu Lai, members of his company spotted a 12-year-old boy out in a rainstorm. He was unarmed and clad only in shorts.

"Somebody caught him up on a hill, and they brought him down and the lieutenant asked who wanted to kill him," Henry told investigators.

Two volunteers stepped forward. One kicked the boy in the stomach. The other took him behind a rock and shot him, according to Henry's statement. They tossed his body in a river and reported him as an enemy combatant killed in action.

Three days later, B Company detained and beat an elderly man suspected of supporting the enemy. He had trouble keeping pace as the soldiers marched him up a steep hill.

"When I turned around, two men had him, one guy had his arms, one guy had his legs and they threw him off the hill onto a bunch of rocks," Henry's statement said.

On Oct. 15, some of the men took a break during a large-scale "search-and-destroy" operation. Henry said he overheard a lieutenant on the radio requesting permission to test-fire his weapon, and went to see what was happening.

He found two soldiers using a Vietnamese man for target practice, Henry said. They had discovered the victim sleeping in a hut and decided to kill him for sport.

"Everybody was taking pot shots at him, seeing how accurate they were," Henry said in his statement.

Back at base camp on Oct. 23, he said, members of the 1st Platoon told him they had ambushed five unarmed women and reported them as enemies killed in action. Later, members of another platoon told him they had seen the bodies.

Tet Offensive

Capt. Donald C. Reh, a 1964 graduate of West Point, took command of B Company in November 1967. Two months later, enemy forces launched a major offensive during Tet, the Vietnamese lunar New Year.

In the midst of the fighting, on Feb. 7, the commander of the 1st Battalion, Lt. Col. William W. Taylor Jr., ordered an assault on snipers hidden in a line of trees in a rural area of Quang Nam province. Five U.S. soldiers were killed. The troops complained bitterly about the order and the deaths, Henry said.

The next morning, the men packed up their gear and continued their sweep of the countryside. Soldiers discovered an unarmed man hiding in a hole and suspected that he had supported the enemy the previous day. A soldier pushed the man in front of an armored personnel carrier, Henry said in his statement.

"They drove over him forward which didn't kill him because he was squirming around, so the APC backed over him again," Henry's statement said.

Then B Company entered a hamlet to question residents and search for weapons. That's where Henry set down his weapon and lighted a cigarette in the shelter of a hut.

A radio operator sat down next to him, and Henry was listening to the chatter. He heard the leader of the 3rd Platoon ask Reh for instructions on what to do with 19 civilians.

"The lieutenant asked the captain what should be done with them. The captain asked the lieutenant if he remembered the op order (operation order) that came down that morning and he repeated the order which was 'kill anything that moves,' " Henry said in his statement. "I was a little shook ... because I thought the lieutenant might do it."

Henry said he left the hut and walked toward Reh. He saw the captain pick up the phone again, and thought he might rescind the order.

Then soldiers pulled a naked woman of about 19 from a dwelling and brought her to where the other civilians were huddled, Henry said.

"She was thrown to the ground," he said in his statement. "The men around the civilians opened fire and all on automatic or at least it seemed all on automatic. It was over in a few seconds. There was a lot of blood and flesh and stuff flying around....

"I looked around at some of my friends and they all just had blank looks on their faces.... The captain made an announcement to all the company, I forget exactly what it was, but it didn't concern the people who had just been killed. We picked up our stuff and moved on."

Henry didn't forget, however. "Thirty seconds after the shooting stopped," he said, "I knew that I was going to do something about it."

Homecoming

For his combat service, Henry earned a Bronze Star with a V for valor, and a Combat Medical Badge, among other awards. A fellow member of his unit said in a sworn statement that Henry regularly disregarded his own safety to save soldiers' lives, and showed "compassion and decency" toward enemy prisoners.

When Henry finished his tour and arrived at Ft. Hood, Texas, in September 1968, he went to see an Army legal officer to report the atrocities he'd witnessed.

The officer advised him to keep quiet until he got out of the Army, "because of the million and one charges you can be brought up on for blinking your eye," Henry says. Still, the legal officer sent him to see a Criminal Investigation Division agent.

The agent was not receptive, Henry recalls.

"He wanted to know what I was trying to pull, what I was trying to put over on people, and so I was just quiet. I told him I wouldn't tell him anything and I wouldn't say anything until I got out of the Army, and I left," Henry says.

Honorably discharged in March 1969, Henry moved to Canoga Park, enrolled in community college and helped organize a campus chapter of Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

Then he ended his silence: He published his account of the massacre in the debut issue of Scanlan's Monthly, a short-lived muckraking magazine, which hit the newsstands on Feb. 27, 1970. Henry held a news conference the same day at the Los Angeles Press Club.

Records show that an Army operative attended incognito, took notes and reported back to the Pentagon.

A faded copy of Henry's brief statement, retrieved from the Army's files, begins:

"On February 8, 1968, nineteen (19) women and children were murdered in Viet-Nam by members of 3rd Platoon, 'B' Company, 1st Battalion, 35th Infantry....

"Incidents similar to those I have described occur on a daily basis and differ one from the other only in terms of numbers killed," he told reporters. A brief article about his remarks appeared inside the Los Angeles Times the next day.

Army investigators interviewed Henry the day after the news conference. His sworn statement filled 10 single-spaced typed pages. Henry did not expect anything to come of it: "I never got the impression they were ever doing anything."

In 1971, Henry joined more than 100 other veterans at the Winter Soldier Investigation, a forum on war crimes sponsored by Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

The FBI put the three-day gathering at a Detroit hotel under surveillance, records show, and Nixon administration officials worked behind the scenes to discredit the speakers as impostors and fabricators.

Although the administration never publicly identified any fakers, one of the organization's leaders admitted exaggerating his rank and role during the war, and a cloud descended on the entire gathering.

"We tried to get as much publicity as we could, and it just never went anywhere," Henry says. "Nothing ever happened."

After years of dwelling on the war, he says, he "finally put it in a closet and shut the door".

The Investigation

Unknown to Henry, Army investigators pursued his allegations, tracking down members of his old unit over the next 3 1/2 years.

Witnesses described the killing of the young boy, the old man tossed over the cliff, the man used for target practice, the five unarmed women, the man thrown beneath the armored personnel carrier and other atrocities.

Their statements also provided vivid corroboration of the Feb. 8, 1968, massacre from men who had observed the day's events from various vantage points.

Staff Sgt. Wilson Bullock told an investigator at Ft. Carson, Colo., that his platoon had captured 19 "women, children, babies and two or three very old men" during the Tet offensive.

"All of these people were lined up and killed," he said in a sworn statement. "When it, the shooting, stopped, I began to return to the site when I observed a naked Vietnamese female run from the house to the huddle of people, saw that her baby had been shot. She picked the baby up and was then shot and the baby shot again."

Gregory Newman, another veteran of B Company, told an investigator at Ft. Myer, Va., that Capt. Reh had issued an order "to search and destroy and kill anything in the village that moved."

Newman said he was carrying out orders to kill the villagers' livestock when he saw a naked girl head toward a group of civilians.

"I saw them begging before they were shot," he recalled in a sworn statement.

Donald R. Richardson said he was at a command post outside the hamlet when he heard a platoon leader on the radio ask what to do with 19 civilians.

"The cpt said something about kill anything that moves and the lt on the other end said 'Their [sic] moving,' " according to Richardson's sworn account. "Just then the gunfire was heard."

William J. Nieset, a rifle squad leader, told investigators that he was standing next to a radio operator and heard Reh say: "My instructions from higher are to kill everything that moves."

Robert D. Miller said he was the radio operator for Lt. Johnny Mack Carter, commander of the 3rd Platoon. Miller said that when Carter asked Reh what to do with the 19 civilians, the captain instructed him to follow the "operation order."

Carter immediately sought two volunteers to shoot the civilians, Miller said under oath.

"I believe everyone knew what was going to happen," he said, "so no one volunteered except one guy known only to me as 'Crazy.' "

"A few minutes later, while the Vietnamese were huddled around in a circle Lt Carter and 'Crazy' started shooting them with their M-16's on automatic," Miller's statement says.

Carter had just left active duty when an investigator questioned him under oath in Palmetto, Fla., in March 1970.

"I do not recall any civilians being picked up and categorically stated that I did not order the killing of any civilians, nor do I know of any being killed," his statement said.

An Army investigator called Reh at Ft. Myer. Reh's attorney called back. The investigator made notes of their conversation: "If the interview of Reh concerns atrocities in Vietnam ... then he had already advised Reh not to make any statement."

As for Lt. Col. Taylor, two soldiers described his actions that day.

Myran Ambeau, a rifleman, said he was standing five feet from the captain and heard him contact the battalion commander, who was in a helicopter overhead. (Ambeau did not identify Reh or Taylor by name.)

"The battalion commander told the captain, 'If they move, shoot them,' " according to a sworn statement that Ambeau gave an investigator in Little Rock, Ark. "The captain verified that he had heard the command, he then transmitted the instruction to Lt Carter.

"Approximately three minutes later, there was automatic weapons fire from the direction where the prisoners were being held."

Gary A. Bennett, one of Reh's radio operators, offered a somewhat different account. He said the captain asked what he should do with the detainees, and the battalion commander replied that it was a "search and destroy mission," according to an investigator's summary of an interview with Bennett.

Bennett said he did not believe the order authorized killing civilians and that, although he heard shooting, he knew nothing about a massacre, the summary says. Bennett refused to provide a sworn statement.

An Army investigator sat down with Taylor at the Army War College in Carlisle, Pa. Taylor said he had never issued an order to kill civilians and had heard nothing about a massacre on the date in question. But the investigator had asked Taylor about events occurring on Feb. 9, 1968 - a day after the incident.

Three and a half years later, an agent tracked Taylor down at Ft. Myer and asked him about Feb. 8. Taylor said he had no memory of the day and did not have time to provide a sworn statement. He said he had a "pressing engagement" with "an unidentified general officer," the agent wrote.

Investigators wrote they could not find Pvt. Frank Bonilla, the man known as "Crazy." The Times reached him at his home on Oahu in March.

Bonilla, now 58 and a hotel worker, says he recalls an order to kill the civilians, but says he does not remember who issued it. "Somebody had a radio, handed it to someone, maybe a lieutenant, said the man don't want to see nobody standing," he said.

Bonilla says he answered a call for volunteers but never pulled the trigger.

"I couldn't do it. There were women and kids," he says. "A lot of guys thought that I had something to do with it because they saw me going up there.... Nope ... I just turned the other way. It was like, 'This ain't happening.' "

Afterward, he says, "I remember sitting down with my head between my knees. Is that for real? Someone said, 'Keep your mouth shut or you're not going home.' "

He says he does not know who did the shooting.

The Outcome

The Criminal Investigation Division assigned Warrant Officer Jonathan P. Coulson in Los Angeles to complete the investigation and write a final report on the "Henry Allegation." He sent his findings to headquarters in Washington in January 1974.

Evidence showed that the massacre did occur, the report said. The investigation also confirmed all but one of the other killings that Henry had described. The one exception was the elderly man thrown off a cliff. Coulson said it could not be determined whether the victim was alive when soldiers tossed him.

The evidence supported murder charges in five incidents against nine "subjects," including Carter and Bonilla, Coulson wrote. Those two carried out the Feb. 8 massacre, along with "other unidentified members of their element," the report said.

Investigators determined that there was not enough evidence to charge Reh with murder, because of conflicting accounts "as to the actual language" he used.

But Reh could be charged with dereliction of duty for failing to investigate the killings, the report said.

Coulson conferred with an Army legal advisor, Capt. Robert S. Briney, about whether the evidence supported charges against Taylor.

They decided it did not. Even if Taylor gave an order to kill the Vietnamese if they moved, the two concluded, "it does not constitute an order to kill the prisoners in the manner in which they were executed."

The War Crimes Working Group records give no indication that action was taken against any of the men named in the report.

Briney, now an attorney in Phoenix, says he has forgotten details of the case but recalls a reluctance within the Army to pursue such charges.

"They thought the war, if not over, was pretty much over. Why bring this stuff up again?" he says.

Years Later

Taylor retired in 1977 with the rank of colonel. In a recent interview outside his home in northern Virginia, he said, "I would not have given an order to kill civilians. It's not in my makeup. I've been in enough wars to know that it's not the right thing to do."

Reh, who left active duty in 1978 and now lives in Northern California, declined to be interviewed by The Times.

Carter, a retired postal worker living in Florida, says he has no memory of his combat experiences. "I guess I've wiped Vietnam and all that out of my mind. I don't remember shooting anyone or ordering anyone to shoot," he says.

He says he does not dispute that a massacre took place. "I don't doubt it, but I don't remember.... Sometimes people just snap."

Henry was re-interviewed by an Army investigator in 1972, and was never contacted again. He drifted away from the antiwar movement, moved north and became a logger in California's Sierra Nevada foothills. He says he had no idea he had been vindicated - until The Times contacted him in 2005.

Last fall, he read the case file over a pot of coffee at his dining room table in a comfortably worn house, where he lives with his wife, Patty.

"I was a wreck for a couple days," Henry, now 59, wrote later in an e-mail. "It was like a time warp that put me right back in the middle of that mess. Some things long forgotten came back to life. Some of them were good and some were not.

"Now that whole stinking war is back. After you left, I just sat in my chair and shook for a couple hours. A slight emotional stress fracture?? Don't know, but it soon passed and I decided to just keep going with this business. If it was right then, then it still is."

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4289

Reputation: 8.16

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:Sorry. Most of What You Think You Know is Wrong. WW II redux.

« Reply #3 on: 2006-08-10 16:10:02 » |

|

Mother do you think they'll drop the bomb? [Pink Floyd 1979]

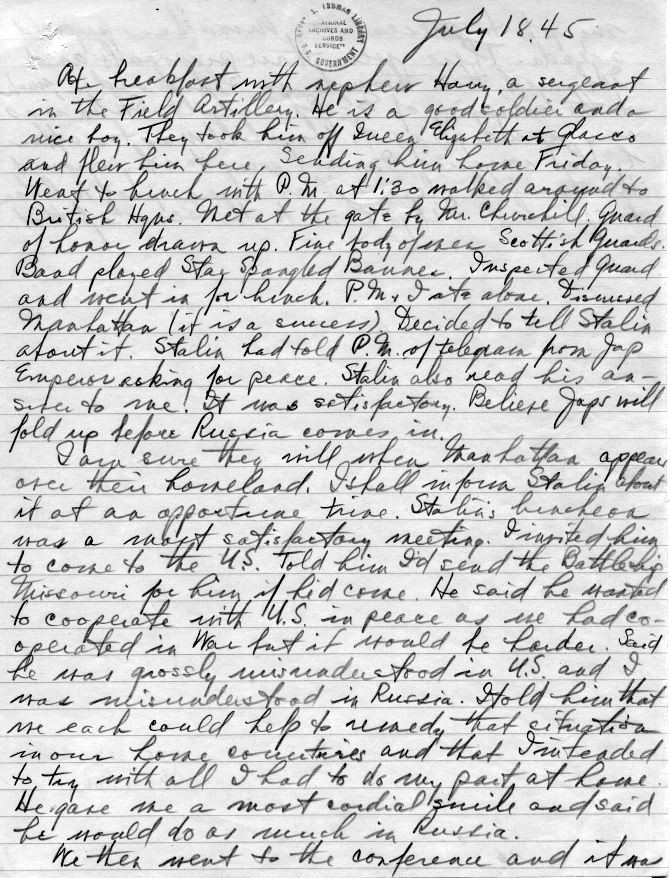

"Stalin had told P.M. of telegram from Jap Emperor asking for peace. Stalin also read his answer to me! It was satisfactory. Believe that Japs will fold up before Russia comes in." - Harry Truman's Diary, prior to the announcement of Truman's determination to use nuclear weapons on Japan and prior to Russia entering the war against Japan, 1945

"Mama's gonna make all of your Nightmares come true" [Pink Floyd 1979]

"If the Germans had dropped atomic bombs on cities instead of us, we would have defined the dropping of atomic bombs on cities as a war crime, and we would have sentenced the Germans who were guilty of this crime to death at Nuremberg and hanged them." Leo Szilard

source: Doug Long

A collection of quotes reflecting the contemporaneous positions of significant decision makers on the decision to eliminate Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

DWIGHT EISENHOWER

"...in [July] 1945... Secretary of War Stimson, visiting my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act. ...the Secretary, upon giving me the news of the successful bomb test in New Mexico, and of the plan for using it, asked for my reaction, apparently expecting a vigorous assent.

"During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of 'face'. The Secretary was deeply perturbed by my attitude..."

- Dwight Eisenhower, Mandate For Change, pg. 380

In a Newsweek interview, Eisenhower again recalled the meeting with Stimson:

"...the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn't necessary to hit them with that awful thing."

- Ike on Ike, Newsweek, 11/11/63

ADMIRAL WILLIAM D. LEAHY

(Chief of Staff to Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman)

"It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.

"The lethal possibilities of atomic warfare in the future are frightening. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children."

- William Leahy, I Was There, pg. 441.

HERBERT HOOVER

On May 28, 1945, Hoover visited President Truman and suggested a way to end the Pacific war quickly: "I am convinced that if you, as President, will make a shortwave broadcast to the people of Japan - tell them they can have their Emperor if they surrender, that it will not mean unconditional surrender except for the militarists - you'll get a peace in Japan - you'll have both wars over."

Richard Norton Smith, An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover, pg. 347.

On August 8, 1945, after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Hoover wrote to Army and Navy Journal publisher Colonel John Callan O'Laughlin, "The use of the atomic bomb, with its indiscriminate killing of women and children, revolts my soul."

quoted from Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb, pg. 635.

"...the Japanese were prepared to negotiate all the way from February 1945...up to and before the time the atomic bombs were dropped; ...if such leads had been followed up, there would have been no occasion to drop the [atomic] bombs."

- quoted by Barton Bernstein in Philip Nobile, ed., Judgment at the Smithsonian, pg. 142

Hoover biographer Richard Norton Smith has written: "Use of the bomb had besmirched America's reputation, he [Hoover] told friends. It ought to have been described in graphic terms before being flung out into the sky over Japan."

Richard Norton Smith, An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover, pg. 349-350.

In early May of 1946 Hoover met with General Douglas MacArthur. Hoover recorded in his diary, "I told MacArthur of my memorandum of mid-May 1945 to Truman, that peace could be had with Japan by which our major objectives would be accomplished. MacArthur said that was correct and that we would have avoided all of the losses, the Atomic bomb, and the entry of Russia into Manchuria."

Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb, pg. 350-351.

GENERAL DOUGLAS MacARTHUR

MacArthur biographer William Manchester has described MacArthur's reaction to the issuance by the Allies of the Potsdam Proclamation to Japan: "...the Potsdam declaration in July, demand[ed] that Japan surrender unconditionally or face 'prompt and utter destruction.' MacArthur was appalled. He knew that the Japanese would never renounce their emperor, and that without him an orderly transition to peace would be impossible anyhow, because his people would never submit to Allied occupation unless he ordered it. Ironically, when the surrender did come, it was conditional, and the condition was a continuation of the imperial reign. Had the General's advice been followed, the resort to atomic weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki might have been unnecessary."

William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880-1964, pg. 512.

Norman Cousins was a consultant to General MacArthur during the American occupation of Japan. Cousins writes of his conversations with MacArthur, "MacArthur's views about the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were starkly different from what the general public supposed." He continues, "When I asked General MacArthur about the decision to drop the bomb, I was surprised to learn he had not even been consulted. What, I asked, would his advice have been? He replied that he saw no military justification for the dropping of the bomb. The war might have ended weeks earlier, he said, if the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the emperor."

Norman Cousins, The Pathology of Power, pg. 65, 70-71.

JOSEPH GREW

(Under Sec. of State)

In a February 12, 1947 letter to Henry Stimson (Sec. of War during WWII), Grew responded to the defense of the atomic bombings Stimson had made in a February 1947 Harpers magazine article:

"...in the light of available evidence I myself and others felt that if such a categorical statement about the [retention of the] dynasty had been issued in May, 1945, the surrender-minded elements in the [Japanese] Government might well have been afforded by such a statement a valid reason and the necessary strength to come to an early clearcut decision.

"If surrender could have been brought about in May, 1945, or even in June or July, before the entrance of Soviet Russia into the [Pacific] war and the use of the atomic bomb, the world would have been the gainer."

Grew quoted in Barton Bernstein, ed.,The Atomic Bomb, pg. 29-32.

JOHN McCLOY

(Assistant Sec. of War)

"I have always felt that if, in our ultimatum to the Japanese government issued from Potsdam [in July 1945], we had referred to the retention of the emperor as a constitutional monarch and had made some reference to the reasonable accessibility of raw materials to the future Japanese government, it would have been accepted. Indeed, I believe that even in the form it was delivered, there was some disposition on the part of the Japanese to give it favorable consideration. When the war was over I arrived at this conclusion after talking with a number of Japanese officials who had been closely associated with the decision of the then Japanese government, to reject the ultimatum, as it was presented. I believe we missed the opportunity of effecting a Japanese surrender, completely satisfactory to us, without the necessity of dropping the bombs."

McCloy quoted in James Reston, Deadline, pg. 500.

RALPH BARD

(Under Sec. of the Navy)

On June 28, 1945, a memorandum written by Bard the previous day was given to Sec. of War Henry Stimson. It stated, in part:

"Following the three-power [July 1945 Potsdam] conference emissaries from this country could contact representatives from Japan somewhere on the China Coast and make representations with regard to Russia's position [they were about to declare war on Japan] and at the same time give them some information regarding the proposed use of atomic power, together with whatever assurances the President might care to make with regard to the [retention of the] Emperor of Japan and the treatment of the Japanese nation following unconditional surrender. It seems quite possible to me that this presents the opportunity which the Japanese are looking for.

"I don't see that we have anything in particular to lose in following such a program." He concluded the memorandum by noting, "The only way to find out is to try it out."

Memorandum on the Use of S-1 Bomb, Manhattan Engineer District Records, Harrison-Bundy files, folder # 77, National Archives (also contained in: Martin Sherwin, A World Destroyed, 1987 edition, pg. 307-308).

Later Bard related, "...it definitely seemed to me that the Japanese were becoming weaker and weaker. They were surrounded by the Navy. They couldn't get any imports and they couldn't export anything. Naturally, as time went on and the war developed in our favor it was quite logical to hope and expect that with the proper kind of a warning the Japanese would then be in a position to make peace, which would have made it unnecessary for us to drop the bomb and have had to bring Russia in...".

quoted in Len Giovannitti and Fred Freed, The Decision To Drop the Bomb, pg. 144-145, 324.

Bard also asserted, "I think that the Japanese were ready for peace, and they already had approached the Russians and, I think, the Swiss. And that suggestion of [giving] a warning [of the atomic bomb] was a face-saving proposition for them, and one that they could have readily accepted." He continued, "In my opinion, the Japanese war was really won before we ever used the atom bomb. Thus, it wouldn't have been necessary for us to disclose our nuclear position and stimulate the Russians to develop the same thing much more rapidly than they would have if we had not dropped the bomb."

War Was Really Won Before We Used A-Bomb, U.S. News and World Report, 8/15/60, pg. 73-75.

LEWIS STRAUSS

(Special Assistant to the Sec. of the Navy)

Strauss recalled a recommendation he gave to Sec. of the Navy James Forrestal before the atomic bombing of Hiroshima:

"I proposed to Secretary Forrestal that the weapon should be demonstrated before it was used. Primarily it was because it was clear to a number of people, myself among them, that the war was very nearly over. The Japanese were nearly ready to capitulate... My proposal to the Secretary was that the weapon should be demonstrated over some area accessible to Japanese observers and where its effects would be dramatic. I remember suggesting that a satisfactory place for such a demonstration would be a large forest of cryptomeria trees not far from Tokyo. The cryptomeria tree is the Japanese version of our redwood... I anticipated that a bomb detonated at a suitable height above such a forest... would lay the trees out in windrows from the center of the explosion in all directions as though they were matchsticks, and, of course, set them afire in the center. It seemed to me that a demonstration of this sort would prove to the Japanese that we could destroy any of their cities at will... Secretary Forrestal agreed wholeheartedly with the recommendation..."

Strauss added, "It seemed to me that such a weapon was not necessary to bring the war to a successful conclusion, that once used it would find its way into the armaments of the world...".

quoted in Len Giovannitti and Fred Freed, The Decision To Drop the Bomb, pg. 145, 325.

PAUL NITZE

(Vice Chairman, U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey)

In 1950 Nitze would recommend a massive military buildup, and in the 1980s he was an arms control negotiator in the Reagan administration. In July of 1945 he was assigned the task of writing a strategy for the air attack on Japan. Nitze later wrote:

"The plan I devised was essentially this: Japan was already isolated from the standpoint of ocean shipping. The only remaining means of transportation were the rail network and intercoastal shipping, though our submarines and mines were rapidly eliminating the latter as well. A concentrated air attack on the essential lines of transportation, including railroads and (through the use of the earliest accurately targetable glide bombs, then emerging from development) the Kammon tunnels which connected Honshu with Kyushu, would isolate the Japanese home islands from one another and fragment the enemy's base of operations. I believed that interdiction of the lines of transportation would be sufficiently effective so that additional bombing of urban industrial areas would not be necessary.

"While I was working on the new plan of air attack... [I] concluded that even without the atomic bomb, Japan was likely to surrender in a matter of months. My own view was that Japan would capitulate by November 1945."

Paul Nitze, From Hiroshima to Glasnost, pg. 36-37 (my emphasis)

The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey group, assigned by President Truman to study the air attacks on Japan, produced a report in July of 1946 that was primarily written by Nitze and reflected his reasoning:

"Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey's opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945 and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated."

quoted in Barton Bernstein, The Atomic Bomb, pg. 52-56.

In his memoir, written in 1989, Nitze repeated,

"Even without the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it seemed highly unlikely, given what we found to have been the mood of the Japanese government, that a U.S. invasion of the islands [scheduled for November 1, 1945] would have been necessary."

Paul Nitze, From Hiroshima to Glasnost, pg. 44-45.

ALBERT EINSTEIN

Einstein was not directly involved in the Manhattan Project (which developed the atomic bomb). In 1905, as part of his Special Theory of Relativity, he made the intriguing point that a relatively large amount of energy was contained in and could be released from a relatively small amount of matter. This became best known by the equation E=mc2. The atomic bomb was not based upon this theory but clearly illustrated it.

In 1939 Einstein signed a letter to President Roosevelt that was drafted by the scientist Leo Szilard. Received by FDR in October of that year, the letter from Einstein called for and sparked the beginning of U.S. government support for a program to build an atomic bomb, lest the Nazis build one first.

Einstein did not speak publicly on the atomic bombing of Japan until a year afterward. A short article on the front page of the New York Times contained his view:

"Prof. Albert Einstein... said that he was sure that President Roosevelt would have forbidden the atomic bombing of Hiroshima had he been alive and that it was probably carried out to end the Pacific war before Russia could participate."

Einstein Deplores Use of Atom Bomb, New York Times, 8/19/46, pg. 1.

Regarding the 1939 letter to Roosevelt, his biographer, Ronald Clark, has noted:

"As far as his own life was concerned, one thing seemed quite clear. 'I made one great mistake in my life,' he said to Linus Pauling, who spent an hour with him on the morning of November 11, 1954, '...when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but there was some justification - the danger that the Germans would make them.'".

Ronald Clark, Einstein: The Life and Times, pg. 620.

LEO SZILARD

(The first scientist to conceive of how an atomic bomb might be made - 1933)

For many scientists, one motivation for developing the atomic bomb was to make sure Germany, well known for its scientific capabilities, did not get it first. This was true for Szilard, a Manhattan Project scientist.

"In the spring of '45 it was clear that the war against Germany would soon end, and so I began to ask myself, 'What is the purpose of continuing the development of the bomb, and how would the bomb be used if the war with Japan has not ended by the time we have the first bombs?".

Szilard quoted in Spencer Weart and Gertrud Weiss Szilard, ed., Leo Szilard: His Version of the Facts, pg. 181.

After Germany surrendered, Szilard attempted to meet with President Truman. Instead, he was given an appointment with Truman's Sec. of State to be, James Byrnes. In that meeting of May 28, 1945, Szilard told Byrnes that the atomic bomb should not be used on Japan. Szilard recommended, instead, coming to an international agreement on the control of atomic weapons before shocking other nations by their use:

"I thought that it would be a mistake to disclose the existence of the bomb to the world before the government had made up its mind about how to handle the situation after the war. Using the bomb certainly would disclose that the bomb existed." According to Szilard, Byrnes was not interested in international control: "Byrnes... was concerned about Russia's postwar behavior. Russian troops had moved into Hungary and Rumania, and Byrnes thought it would be very difficult to persuade Russia to withdraw her troops from these countries, that Russia might be more manageable if impressed by American military might, and that a demonstration of the bomb might impress Russia." Szilard could see that he wasn't getting though to Byrnes; "I was concerned at this point that by demonstrating the bomb and using it in the war against Japan, we might start an atomic arms race between America and Russia which might end with the destruction of both countries.".

Szilard quoted in Spencer Weart and Gertrud Weiss Szilard, ed., Leo Szilard: His Version of the Facts, pg. 184.

Two days later, Szilard met with J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head scientist in the Manhattan Project. "I told Oppenheimer that I thought it would be a very serious mistake to use the bomb against the cities of Japan. Oppenheimer didn't share my view." "'Well, said Oppenheimer, 'don't you think that if we tell the Russians what we intend to do and then use the bomb in Japan, the Russians will understand it?'. 'They'll understand it only too well,' Szilard replied, no doubt with Byrnes's intentions in mind."

Szilard quoted in Spencer Weart and Gertrud Weiss Szilard, ed., Leo Szilard: His Version of the Facts, pg. 185; also William Lanouette, Genius In the Shadows: A Biography of Leo Szilard, pg. 266-267.

THE FRANCK REPORT: POLITICAL AND SOCIAL PROBLEMS

The race for the atomic bomb ended with the May 1945 surrender of Germany, the only other power capable of creating an atomic bomb in the near future. This led some Manhattan Project scientists in Chicago to become among the first to consider the long-term consequences of using the atomic bomb against Japan in World War II. Their report came to be known as the Franck Report, and included major contributions from Leo Szilard (referred to above). Although an attempt was made to give the report to Sec. of War Henry Stimson, it is unclear as to whether he ever received it.

International control of nuclear weapons for the prevention of a larger nuclear war was the report's primary concern:

"If we consider international agreement on total prevention of nuclear warfare as the paramount objective, and believe that it can be achieved, this kind of introduction of atomic weapons [on Japan] to the world may easily destroy all our chances of success. Russia... will be deeply shocked. It will be very difficult to persuade the world that a nation which was capable of secretly preparing and suddenly releasing a weapon, as indiscriminate as the rocket bomb and a thousand times more destructive, is to be trusted in its proclaimed desire of having such weapons abolished by international agreement.".

The Franck Committee, which could not know that the Japanese government would approach Russia in July to try to end the war, compared the short-term possible saving of lives by using the bomb on Japan with the long-term possible massive loss of lives in a nuclear war:

"...looking forward to an international agreement on prevention of nuclear warfare - the military advantages and the saving of American lives, achieved by the sudden use of atomic bombs against Japan, may be outweighed by the ensuing loss of confidence and wave of horror and repulsion, sweeping over the rest of the world...".