Author

Author

|

Topic: Computers in the Ancient World: The Antikythera Mechanism (Read 4280 times) |

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4288

Reputation: 8.94

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Computers in the Ancient World: The Antikythera Mechanism

« on: 2006-11-30 15:02:35 » |

|

An Ancient Computer Surprises Scientists

Source: The New York Times

Authors: John Noble Wilford

Dated: 2006-11-29

Alterations: Hermit converted references from BC to BCE and AD to CE.

External References:

Abstract of Nature Article

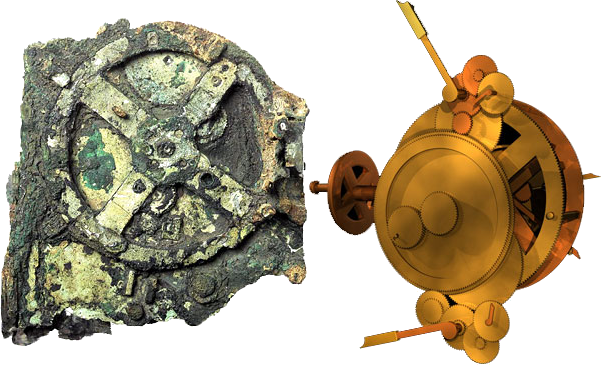

Caption: Fragments of the Antikythera Mechanism, left, have now been examined with the latest in high-resolution imaging systems and three-dimensional X-ray tomography. School of Physics and Astronomy, Cardiff University

A computer in antiquity would seem to be an anachronism, like Athena ordering takeout on her cellphone.

But a century ago, pieces of a strange mechanism with bronze gears and dials were recovered from an ancient shipwreck off the coast of Greece. Historians of science concluded that this was an instrument that calculated and illustrated astronomical information, particularly phases of the Moon and planetary motions, in the second century BCE.

The Antikythera Mechanism, sometimes called the world’s first computer, has now been examined with the latest in high-resolution imaging systems and three-dimensional X-ray tomography. A team of British, Greek and American researchers was able to decipher many inscriptions and reconstruct the gear functions, revealing, they said, "an unexpected degree of technical sophistication for the period."

The researchers, led by Tony Freeth and Mike G. Edmunds, both of the University of Cardiff, Wales, are reporting the results of their study in Thursday’s issue of the journal Nature.

They said their findings showed that the inscriptions related to lunar-solar motions and the gears were a mechanical representation of the irregularities of the Moon’s orbital course across the sky, as theorized by the astronomer Hipparchos. They established the date of the mechanism at 150-100 BCE.

The Roman ship carrying the artifacts sank off the island of Antikythera around 65 BCE. Some evidence suggests that the ship had sailed from Rhodes. The researchers speculated that Hipparchos, who lived on Rhodes, might have had a hand in designing the device.

In another article in the journal, a scholar not involved in the research, François Charette of the University of Munich museum, in Germany, said the new interpretation of the Antikythera Mechanism "is highly seductive and convincing in all of its details." It is not the last word, he concluded, "but it does provide a new standard, and a wealth of fresh data, for future research."

Historians of technology think the instrument is technically more complex than any known device for at least a millennium afterward.

The mechanism, presumably used in preparing calendars for seasons of planting and harvesting and fixing religious festivals, had at least 30, possibly 37, hand-cut bronze gear-wheels, the researchers reported. An ingenious pin-and-slot device connecting two gear-wheels induced variations in the representation of lunar motions according to the Hipparchos model of the Moon’s elliptical orbit around Earth.

The functions of the mechanism were determined by the numbers of teeth in the gears. The 53-tooth count of certain gears, the researchers said, was "powerful confirmation of our proposed model of Hipparchos’ lunar theory."

The detailed imaging revealed more than twice as many inscriptions as had been recognized from earlier examinations. Some of these appeared to relate to planetary as well as lunar motions. Perhaps, the researchers said, the mechanism also had gearings to predict the positions of known planets.

Dr. Charette noted that more than 1,000 years elapsed before instruments of such complexity are known to have re-emerged. A few artifacts and some Arabic texts suggest that simpler geared calendrical devices had existed, particularly in Baghdad around 900 CE.

It seems clear, Dr. Charette said, that "much of the mind-boggling technological sophistication available in some parts of the Hellenistic and Greco-Roman world was simply not transmitted further," adding, "The gear-wheel, in this case, had to be reinvented."

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4288

Reputation: 8.94

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:Computers in the Ancient World: The Antikythera Mechanism

« Reply #1 on: 2006-11-30 15:03:37 » |

|

Early Astronomical ‘Computer’ Found to Be Technically Complex

Source: The New York Times

Authors: John Noble Wilford

Dated: 2006-11-30

Alterations: Hermit converted references from BC to BCE and AD to CE.

External References:

Abstract of Nature Article

A computer in antiquity would seem to be an anachronism, like Athena ordering takeout on her cellphone.

But a century ago, pieces of a strange mechanism with bronze gears and dials were recovered from an ancient shipwreck off the coast of Greece. Historians of science concluded that this was an instrument that calculated and illustrated astronomical information, particularly phases of the Moon and planetary motions, in the second century BCE.

The instrument, the Antikythera Mechanism, sometimes called the world’s first computer, has now been examined with the latest in high-resolution imaging systems and three-dimensional X-ray tomography. A team of British, Greek and American researchers deciphered inscriptions and reconstructed the gear functions, revealing "an unexpected degree of technical sophistication for the period," it said.

The researchers, led by the mathematician and filmmaker Tony Freeth and the astronomer Mike G. Edmunds, both of the University of Cardiff, Wales, are reporting their results today in the journal Nature.

They said their findings showed that the inscriptions related to lunar-solar motions, and the gears were a representation of the irregularities of the Moon’s orbital course, as theorized by the astronomer Hipparchos. They established the date of the mechanism at 150-100 BCE.

The Roman ship carrying the artifacts sank off the island of Antikythera about 65 BCE. Some evidence suggests it had sailed from Rhodes. The researchers said that Hipparchos, who lived on Rhodes, might have had a hand in designing the device.

In another Nature article, a scholar not involved in the research, François Charette of the University of Munich museum, in Germany, said the new interpretation of the mechanism "is highly seductive and convincing in all of its details." It is not the last word, he said, "but it does provide a new standard, and a wealth of fresh data, for future research."

Technology historians say the instrument is technically more complex than any known for at least a millennium afterward. Earlier examinations of the instrument, mainly in the 1970s by Derek J. de Solla Price, a Yale historian who died in 1983, led to similar findings, but they were generally disputed or ignored.

The hand-operated mechanism, presumably used in preparing calendars for planting and harvesting and fixing religious festivals, had at least 30, possibly 37, hand-cut bronze gear-wheels, the researchers said. A pin-and-slot device connecting two gear-wheels induced variations in the representation of lunar motions according to the Hipparchos model of the Moon’s elliptical orbit around Earth.

The numbers of teeth in the gears dictated the functions of the mechanism. The 53-tooth count of certain gears, the team said, was "powerful confirmation of our proposed model of Hipparchos’ lunar theory." The detailed imaging revealed more than twice the inscriptions recognized earlier. Some of these appeared to relate to planetary and lunar motions. Perhaps, the team said, the mechanism also had gearings to predict the positions of known planets.

Dr. Charette noted that more than 1,000 years elapsed before instruments of such complexity are known to have re-emerged. A few artifacts and some Arabic texts suggest that simpler geared calendrical devices had existed, particularly in Baghdad around A.D. 900.

It seems clear, he said, that "much of the mind-boggling technological sophistication available in some parts of the Hellenistic and Greco-Roman world was simply not transmitted further."

"The gear-wheel, in this case,” he added, “had to be reinvented."

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4288

Reputation: 8.94

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:Computers in the Ancient World: The Antikythera Mechanism

« Reply #2 on: 2006-11-30 15:31:47 » |

|

Decoding the ancient Greek astronomical calculator known as the Antikythera Mechanism

Source: Nature 444, 587-591 (30 November 2006) | doi:10.1038/nature05357; Received 10 August 2006; Accepted 17 October 2006

Authors: T. Freeth1,2, Y. Bitsakis3,5, X. Moussas3, J. H. Seiradakis4, A. Tselikas5, H. Mangou6, M. Zafeiropoulou6, R. Hadland7, D. Bate7, A. Ramsey7, M. Allen7, A. Crawley7, P. Hockley7, T. Malzbender8, D. Gelb8, W. Ambrisco9 and M. G. Edmunds1

Dated: 2006-11-30

Alterations: Hermit converted references from BC to BCE and AD to CE.

The Antikythera Mechanism is a unique Greek geared device, constructed around the end of the second century bc. It is known1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 that it calculated and displayed celestial information, particularly cycles such as the phases of the moon and a luni-solar calendar. Calendars were important to ancient societies10 for timing agricultural activity and fixing religious festivals. Eclipses and planetary motions were often interpreted as omens, while the calm regularity of the astronomical cycles must have been philosophically attractive in an uncertain and violent world. Named after its place of discovery in 1901 in a Roman shipwreck, the Antikythera Mechanism is technically more complex than any known device for at least a millennium afterwards. Its specific functions have remained controversial11, 12, 13, 14 because its gears and the inscriptions upon its faces are only fragmentary. Here we report surface imaging and high-resolution X-ray tomography of the surviving fragments, enabling us to reconstruct the gear function and double the number of deciphered inscriptions. The mechanism predicted lunar and solar eclipses on the basis of Babylonian arithmetic-progression cycles. The inscriptions support suggestions of mechanical display of planetary positions9, 14, 15, now lost. In the second century BCE, Hipparchos developed a theory to explain the irregularities of the Moon's motion across the sky caused by its elliptic orbit. We find a mechanical realization of this theory in the gearing of the mechanism, revealing an unexpected degree of technical sophistication for the period.

1. Cardiff University, School of Physics and Astronomy, Queens Buildings, The Parade, Cardiff CF24 3AA, UK

2. Images First Ltd, 10 Hereford Road, South Ealing, London W5 4SE, UK

3. National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Department of Astrophysics, Astronomy and Mechanics, Panepistimiopolis, GR-15783, Zographos, Greece

4. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Physics, Section of Astrophysics, Astronomy and Mechanics, GR-54124 Thessaloniki, Greece

5. Centre for History and Palaeography, National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation, P. Skouze 3, GR-10560 Athens, Greece

6. National Archaeological Museum of Athens, 1 Tositsa Str., GR-10682 Athens, Greece

7. X-Tek Systems Ltd, Tring Business Centre, Icknield Way, Tring, Hertfordshire HP23 4JX, UK

8. Hewlett-Packard Laboratories, 1501 Page Mill Road, Palo Alto, California 94304, USA

9. Foxhollow Technologies Inc., 740 Bay Road, Redwood City, California 94063, USA

Correspondence to: M. G. Edmunds1 Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.G.E. (Email: mge@astro.cf.ac.uk).

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4288

Reputation: 8.94

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:Computers in the Ancient World: The Antikythera Mechanism

« Reply #3 on: 2006-11-30 16:12:54 » |

|

Ancient calculator demystified at last

Greeks’ 2,100-year-old Antikythera Mechanism was used in astronomy

Source: LiveScience.com

Authors: Ker Than

Dated: 2006-11-29

Caption: This computer-generated reconstruction shows the front and the back of the ancient Antikythera Mechanism. Antikythera Mechanism Research Project (School of Physics and Astronomy, Cardiff University)

Scientists have finally demystified the incredible workings of a 2,100-year-old astronomical calculator built by ancient Greeks.

A new analysis of the Antikythera Mechanism, a clocklike machine consisting of more than 30 precise, hand-cut bronze gears, show it to be more advanced than previously thought — so much so that nothing comparable was built for another thousand years.

"This device is just extraordinary, the only thing of its kind," said study leader Mike Edmunds of Cardiff University in Wales. "The design is beautiful, the astronomy is exactly right … In terms of historical and scarcity value, I have to regard this mechanism as being more valuable than the Mona Lisa."

The researchers used three-dimensional X-ray scanners to reconstruct the workings of the device's gears, and high-resolution surface imaging to enhance faded inscriptions on its surface.

Precise astronomy

The new analysis reveals that the device's front dials had pointers for the sun and moon — called the "golden little sphere" and "little sphere," respectively — and markings which coincided with the zodiac and solar calendars. The back dials, meanwhile, appear to have been used for predicting solar and lunar eclipses.

The researchers also show that the device could mechanically replicate the irregular motions of the moon, caused by its elliptical orbit around Earth, using a clever design involving two superimposed gear-wheels, one slightly off-center, that are connected by a pin-and-slot device.

The team was also able to pin down the device's construction date more precisely. Radiocarbon dating suggested it was built around 65 BCE, but newly revealed lettering on the machine indicate a slightly older construction date of 150 to 100 BCE. The team's reconstruction also involves 37 gear wheels, seven of which are hypothetical.

"In the face of fragmentary material evidence, such guesswork is inevitable. But the new model is highly seductive, and convincing in all of its detail," Francois Charette, a researcher at the Ludwig-Maximilians University in Germany who was not involved in the study, wrote in a related article in the journal Nature.

Discovered in 1900

Pieces of the calculating machine were discovered by sponge divers exploring the remains of an ancient shipwreck off the tiny island of Antikythera in 1900. For decades, scientists have been trying to figure out how the device's 80 fragmented pieces fit together and unlock its workings.

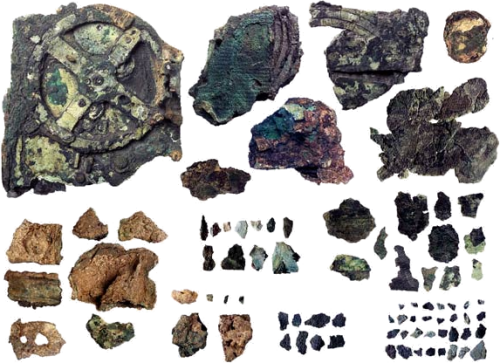

Caption: About 80 pieces of the Antikythera Mechanism were recovered from a shipwreck more than a century ago. AFP - Getty Images

Previous reconstructions suggested the Antikythera Mechanism was about the size of a shoebox, with dials on the outside and a complex assembly of bronze gear wheels within. By winding a knob on its side, the positions of the sun, moon, Mercury and Venus could be determined for any chosen date. Newly revealed inscriptions also appear to confirm previous speculations that the device could also calculate the positions of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn — the other planets known at the time.

The international team, led by Edmunds and Tony Freeth, also of Cardiff University, included astronomers, mathematicians, computer experts, script analysts and conservation experts from Britain, Greece and the United States.

The researchers plan to create a computer model of how the Antikythera Mechanism worked and eventually a working replica.

The team's findings will be presented in a two-day international conference in Athens and published in Thursday's issue of Nature.

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4288

Reputation: 8.94

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:Computers in the Ancient World: The Antikythera Mechanism

« Reply #4 on: 2006-11-30 18:14:20 » |

|

In search of lost time

Source: Nature

Authors: Jo Marchant (News Editor Nature)

Dated: 2006-11-29 doi:10.1038/444534a

Alterations: Hermit converted references from BC to BCE and AD to CE. Removed external links to articles requiring registration.

The ancient Antikythera Mechanism doesn't just challenge our assumptions about technology transfer over the ages — it gives us fresh insights into history itself.

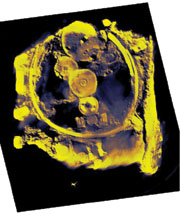

It looks like something from another world — nothing like the classical statues and vases that fill the rest of the echoing hall. Three flat pieces of what looks like green, flaky pastry are supported in perspex cradles. Within each fragment, layers of something that was once metal have been squashed together, and are now covered in calcareous accretions and various corrosions, from the whitish tin oxide to the dark bluish green of copper chloride. This thing spent 2,000 years at the bottom of the sea before making it to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, and it shows.

Caption: The Antikythera Mechanism at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. J. Marchant Antikythera Mechanism Research Project (School of Physics and Astronomy, Cardiff University)

But it is the details that take my breath away. Beneath the powdery deposits, tiny cramped writing is visible along with a spiral scale; there are traces of gear-wheels edged with jagged teeth. Next to the fragments an X-ray shows some of the object's internal workings. It looks just like the inside of a wristwatch.

This is the Antikythera Mechanism. These fragments contain at least 30 interlocking gear-wheels, along with copious astronomical inscriptions. Before its sojourn on the sea bed, it computed and displayed the movement of the Sun, the Moon and possibly the planets around Earth, and predicted the dates of future eclipses. It's one of the most stunning artefacts we have from classical antiquity.

No earlier geared mechanism of any sort has ever been found. Nothing close to its technological sophistication appears again for well over a millennium, when astronomical clocks appear in medieval Europe. It stands as a strange exception, stripped of context, of ancestry, of descendants.

Considering how remarkable it is, the Antikythera Mechanism has received comparatively scant attention from archaeologists or historians of science and technology, and is largely unappreciated in the wider world. A virtual reconstruction of the device, published by Mike Edmunds and his colleagues in this week's Nature (see 'Decoding the ancient Greek astronomical calculator known as the Antikythera Mechanism'), may help to change that. With the help of pioneering three-dimensional images of the fragments' innards, the authors present something close to a complete picture of how the device worked, which in turn hints at who might have been responsible for building it.

But I'm also interested in finding the answer to a more perplexing question — once the technology arose, where did it go to? The fact that such a sophisticated technology appears seemingly out of the blue is perhaps not that surprising — records and artefacts from 2,000 years ago are, after all, scarce. More surprising, to an observer from the progress-obsessed twenty-first century, is the apparent lack of a subsequent tradition based on the same technology — of ever better clockworks spreading out round the world. How can the capacity to build a machine so magnificent have passed through history with no obvious effects?

Astronomic leaps

| To get an idea of what the mechanism looked like before it had the misfortune to find itself on a sinking ship, I went to see Michael Wright, a curator at the Science Museum in London for more than 20 years and now retired. Stepping into Wright's workshop in Hammersmith is a little like stepping into the workshop where H. G. Wells' time machine was made. Every inch of floor, wall, shelf and bench space is covered with models of old metal gadgets and devices, from ancient Arabic astrolabes to twentieth-century trombones. Over a cup of tea he shows me his model of the Antikythera Mechanism as it might have been in his pomp. The model and the scholarship it embodies have consumed much of his life. (see 'Raised from the depths' [infra]). |

Caption: Model success: Michael Wright devoted his life to decoding and replicating the Antikythera Mechanism. A. Wright |

To get an idea of what the mechanism looked like before it had the misfortune to find itself on a sinking ship, I went to see Michael Wright, a curator at the Science Museum in London for more than 20 years and now retired. Stepping into Wright's workshop in Hammersmith is a little like stepping into the workshop where H. G. Wells' time machine was made. Every inch of floor, wall, shelf and bench space is covered with models of old metal gadgets and devices, from ancient Arabic astrolabes to twentieth-century trombones. Over a cup of tea he shows me his model of the Antikythera Mechanism as it might have been in his pomp. The model and the scholarship it embodies have consumed much of his life (see 'Raised from the depths').

The mechanism is contained in a squarish wooden case a little smaller than a shoebox. On the front are two metal dials (brass, although the original was bronze), one inside the other, showing the zodiac and the days of the year. Metal pointers show the positions of the Sun, the Moon and five planets visible to the naked eye. I turn the wooden knob on the side of the box and time passes before my eyes: the Moon makes a full revolution as the Sun inches just a twelfth of the way around the dial. Through a window near the centre of the dial peeks a ball painted half black and half white, spinning to show the Moon's changing phase.

On the back of the box are two spiral dials, one above the other. A pointer at the centre of each traces its way slowly around the spiral groove like a record stylus. The top dial, Wright explains, shows the Metonic cycle — 235 months fitting quite precisely into 19 years. The lower spiral, according to the research by Edmunds and his colleagues, was divided into 223, reflecting the 223-month period of the Saros cycle, which is used to predict eclipses.

To show me what happens inside, Wright opens the case and starts pulling out the wheels. There are 30 known gear-wheels in the Antikythera Mechanism, the biggest taking up nearly the entire width of the box, the smallest less than a centimetre across. They all have triangular teeth, anything from 15 to 223 of them, and each would have been hand cut from a single sheet of bronze. Turning the side knob engages the big gear-wheel, which goes around once for every year, carrying the date hand. The other gears drive the Moon, Sun and planets and the pointers on the Metonic and Saros spirals.

To see the model in action is to want to find out who had the ingenuity to design the original. Unfortunately, none of the copious inscriptions is a signature. But there are other clues. Coins found at the site by Jacques Cousteau in the 1970s have allowed the shipwreck to be dated sometime shortly after 85 BCE. The inscriptions on the device itself suggest it might have been in use for at least 15 or 20 years before that, according to the Edmunds paper.

|

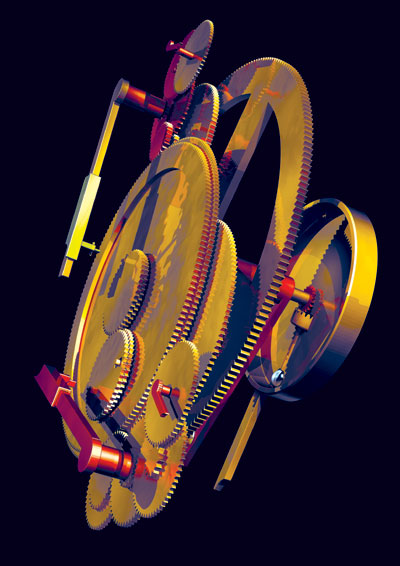

Caption: Gearing up: this reconstruction shows, among other things, the offset wheels of the Moon's nine-year cycle (lower left). Antikythera Mechanism Research Project (School of Physics and Astronomy, Cardiff University) |

The ship was carrying a rich cargo of luxury goods, including statues and silver coins from Pergamon on the coast of Asia Minor and vases in the style of Rhodes, a rich trading port at the time. It went down in the middle of a busy shipping route from the eastern to western Aegean, and it seems a fair bet that it was heading west for Rome, which had by that time become the dominant power in the Mediterranean and had a ruling class that loved Greek art, philosophy and technology.

The Rhodian vases are telling clues, because Rhodes was the place to be for astronomy in the first and second centuries BCE. Hipparchus, arguably the greatest Greek astronomer, is thought to have worked on the island from around 140 BCE until his death in around 120 BCE. Later the philosopher Posidonius set up an astronomy school there that continued Hipparchus' tradition; it is within this tradition that Edmunds and his colleagues think the mechanism originated. Circumstantial evidence is provided by Cicero, the first-century BCE Roman lawyer and consul. Cicero studied on Rhodes and wrote later that Posidonius had made an instrument "which at each revolution reproduces the same motions of the Sun, the Moon and the five planets that take place in the heavens every day and night". The discovery of the Antikythera Mechanism makes it tempting to believe the story is true.

And Edmunds now has another reason to think the device was made by Hipparchus or his followers on Rhodes. His team's three-dimensional reconstructions of the fragments have turned up a new aspect of the mechanism that is both stunningly clever and directly linked to work by Hipparchus. |

Caption: Inside out: computer tomography of the main fragment allowed for accurate modelling. Antikythera Mechanism Research Project (School of Physics and Astronomy, Cardiff University) |

One of the wheels connected to the main drive wheel moves around once every nine years. Fixed on to it is a pair of small wheels, one of which sits almost — but not exactly — on top of the other. The bottom wheel has a pin sticking up from it, which engages with a slot in the wheel above. As the bottom wheel turns, this pin pushes the top wheel round. But because the two wheels aren't centred in the same place, the pin moves back and forth within the upper slot. As a result, the movement of the upper wheel speeds up and slows down, depending on whether the pin is a little farther in towards the centre or a little farther out towards the tips of the teeth.

The researchers realized that the ratios of the gear-wheels involved produce a motion that closely mimics the varying motion of the Moon around Earth, as described by Hipparchus. When the Moon is close to us it seems to move faster. And the closest part of the Moon's orbit itself makes a full rotation around the Earth about every nine years. Hipparchus was the first to describe this motion mathematically, working on the idea that the Moon's orbit, although circular, was centred on a point offset from the centre of Earth that described a nine-year circle. In the Antikythera Mechanism, this theory is beautifully translated into mechanical form. "It's an unbelievably sophisticated idea," says Tony Freeth, a mathematician who worked out most of the mechanics for Edmunds' team. "I don't know how they thought of it."

"I'm very surprised to find a mechanical representation of this," adds Alexander Jones, a historian of astronomy at the University of Toronto, Canada. He says the Antikythera Mechanism has had little impact on the history of science so far. "But I think that's about to change. This was absolutely state of the art in astronomy at the time."

Wright believes that similar mechanisms modelled the motions of the five known planets, as well as of the Sun, although this part of the device has been lost. As he cranks the gears of his model to demonstrate, and the days, months and years pass, each pointer alternately lags behind and picks up speed to mimic the astronomical wanderings of the appropriate sphere.

Greek tragedy

Almost everyone who has studied the mechanism agrees it couldn't have been a one-off — it would have taken practice, perhaps over several generations, to achieve such expertise. Indeed, Cicero wrote of a similar mechanism that was said to have been built by Archimedes. That one was purportedly stolen in 212 BCE by the Roman general Marcellus when Archimedes was killed in the sacking of the Sicilian city of Syracuse. The device was kept as an heirloom in Marcellus' family: as a friend of the family, Cicero may indeed have seen it.

So where are the other examples? A model of the workings of the heavens might have had value to a cultivated mind. Bronze had value for everyone. Most bronze artefacts were eventually melted down: the Athens museum has just ten major bronze statues from ancient Greece, of which nine are from shipwrecks. So in terms of the mechanism, "we're lucky we have one", points out Wright. "We only have this because it was out of reach of the scrap-metal man."

But ideas cannot be melted down, and although there are few examples, there is some evidence that techniques for modelling the cycles in the sky with geared mechanisms persisted in the eastern Mediterranean. A sixth-century CE Byzantine sundial brought to Wright at the Science Museum has four surviving gears and would probably have used at least eight to model the positions of the Sun and Moon in the sky. The rise of Islam saw much Greek work being translated into Arabic in the eighth and ninth centuries CE, and it seems quite possible that a tradition of geared mechanisms continued in the caliphate. Around 1000 CE, the Persian scholar al-Biruni described a "box of the Moon" very similar to the sixth-century device. There's an Arabic-inscribed astrolabe dating from 1221–22 currently in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford, UK, which used seven gears to model the motion of the Sun and Moon.

But to get anything close to the Antikythera Mechanism's sophistication you have to wait until the fourteenth century, when mechanical clockwork appeared all over western Europe. "You start to get a rash of clocks," says Wright. "And as soon as you get clocks, they are being used to drive astronomical displays." Early examples included the St Albans clock made by Richard Wallingford in around 1330 and a clock built by Giovanni de'Dondi a little later in Padua, Italy, both of which were huge astronomical display pieces with elaborate gearing behind the main dial to show the position of the Sun, Moon, planets and (in the case of the Padua clock) the timing of eclipses. The time-telling function seems almost incidental.

It could be argued that the similarities between the medieval technology and that of classical Greece represent separate discoveries of the same thing — a sort of convergent clockwork evolution. Wright, though, favours the idea that they are linked by an unbroken tradition: "I find it as easy to believe that this technology survived unrecorded, as to believe that it was reinvented in so similar a form." The timing of the shift to the West might well have been driven by the fall of Baghdad to the Mongols in the thirteenth century, after which much of the caliphate's knowledge spread to Europe. Shortly after that, mechanical clocks appeared in the West, although nobody knows exactly where or how. It's tempting to think that some mechanisms, or at least the ability to build them, came west at the same time. As François Charette, a historian of science at Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, Germany, points out, "for the translation of technology, you can't rely solely on texts". Most texts leave out vital technical details, so you need skills to be transmitted directly.

But if the tradition of geared mechanisms to show astronomical phenomena really survived for well over a millennium, the level of achievement within that tradition was at best static. The clockwork of medieval Europe became more sophisticated and more widely applied fairly quickly; in the classical Mediterranean, with the same technology available, nothing remotely similar happened. Why didn't anyone do anything more useful with it in all that time? More specifically, why didn't anyone work out earlier what the gift of hindsight seems to make obvious — that clockwork would be a good thing to make clocks with?

Serafina Cuomo, a historian of science at Imperial College, London, thinks that it all depends on what you see as 'useful'. The Greeks weren't that interested in accurate timekeeping, she says. It was enough to tell the hour of the day, which the water-driven clocks of the time could already do fairly well. But they did value knowledge, power and prestige. She points out that there are various descriptions of mechanisms driven by hot air or water — and gears. But instead of developing a steam engine, say, the devices were used to demonstrate philosophical principles. The machines offered a deeper understanding of cosmic order, says David Sedley, a classicist at the University of Cambridge, UK. "There's nothing surprising about the fact that their best technology was used for demonstrating the laws of astronomy. It was deep-rooted in their culture."

Another, not mutually exclusive, theory is that devices such as the Antikythera Mechanism were signifiers of social status. Cuomo points out that demonstrating wondrous devices brought social advancement. "They were trying to impress their peers," she says. "For them, that was worth doing." And the Greek élite was not the only potential market. Rich Romans were eager for all sorts of Greek sophistication — they imported philosophers for centuries.

In the meantime, Edmunds' Antikythera team plans to keep working on the mechanism — there are further inscriptions to be deciphered and the possibility that more fragments could be found. This week the researchers are hosting a conference in Athens that they hope will yield fresh leads. A few minutes' walk from the National Archaeological Museum, Edmunds' colleagues from the University of Athens, Yanis Bitsakis and Xenophon Moussas, treat me to a dinner of aubergine and fried octopus, and explain why they would one day like to devote an entire museum to the story of the fragments.

"It's the same way that we would do things today, it's like modern technology," says Bitsakis. "That's why it fascinates people." What fascinates me is that where we see the potential of that technology to measure time accurately and make machines do work, the Greeks saw a way to demonstrate the beauty of the heavens and get closer to the gods.

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

Hermit

Archon

Posts: 4288

Reputation: 8.94

Rate Hermit

Prime example of a practically perfect person

|

|

Re:Computers in the Ancient World: The Antikythera Mechanism

« Reply #5 on: 2006-11-30 18:52:40 » |

|

Raised from the depths

Annex to "In search of lost time" [supra]

Source: Stupid unlinkable javascript pop-up box linked to "In search of lost time" [supra] Nature

Authors: Jo Marchant (News Editor Nature)

Dated: 2006-11-29 doi:10.1038/444534a

In 1900 a party of Greek sponge divers sought shelter from a storm in the lee of the barren, rocky islet of Antikythera. Once the winds had eased, Elias Stadiatis dived 42 metres to a rocky shelf to look for late additions to his hard-earned haul. Instead of sponges nestled on the sea bed, the shape of a great ship loomed out of the blue. After grabbing the larger-than-life arm of a bronze figure as proof of his find, he returned to the surface to inform his companions. The Antikythera wreck was to yield a stunning collection of bronze and marble statues, pottery, glassware, jewellery and coins; it was also to claim the life of one of the divers, not yet aware of the risk of the bends when diving with an oxygen hose.

As busy museum staff struggled to piece together statues and vases, a formless, corroded lump of bronze and wood lay unnoticed. But as the wood dried and shrivelled, the lump cracked open, and on 17 May 1902, archaeologist Valerios Stais noticed that there were gear-wheels inside.

The gears elicited interest, but it was not until investigations delved beneath the surface that the box started to yield its secrets. The British science historian Derek de Solla Price and the Greek nuclear physicist Charalampos Karakalos made X- and gamma-ray images of the fragments in 1971. Karakalos and his wife Emily painstakingly counted the visible teeth; in 1974 Price published a heroic 70-page account of the machine (D. de S. Price Trans. Am. Phil. Soc., New Ser. 64, 1–70; 1974).

"Price really put the mechanism on the map," says Tony Freeth, co-author of a new reconstruction of the device (see page 587). "He understood the essence of what it was — an astronomical computer." But Price massaged some of the data (much to the annoyance of Karakalos and his wife), and his reconstruction was unnecessarily complicated — perhaps too complicated for historians and archaeologists. They largely ignored Price's work, and he died in 1983.

That same year, a Lebanese man walked into the Science Museum in London with the pieces of another ancient mechanism in his pocket. Curator Michael Wright realized the device was a Byzantine sundial from the sixth century AD, which also contained a simple geared mechanism that drove pointers showing the position of the Moon and Sun in the sky. Studying the astronomically enhanced sundial led Wright to Price's treatment of the Antikythera Mechanism, in which he saw serious holes.

Caption: Location of the rocky islet of Antikythera. Nature

Wright ended up working with Allan Bromley, a computer scientist at Sydney University in Australia who had become interested in the Antikythera Mechanism at around the same time. Bromley wanted to study the machine with X-ray tomography, which assembles a sheaf of cross-sections of its subject. As the fragments could not be moved from the museum, and Bromley didn't have the money to ship a tomography machine to Athens, Wright used his tool-making skills to build a crude tomograph in situ. The two researchers took around 700 images of the fragments, and Wright has been working on a reconstruction that supercedes Price's ever since.

Caption: Unidentified subject with reconstruction of the Antikythera Mechanism. Nature

In the meantime, Mike Edmunds, an astrophysicist at Cardiff University, UK, and his friend Tony Freeth, a mathematician-turned-film-maker living in London, decided the mechanism would make a fantastic subject for a documentary. But their efforts soon turned to discovering more about how the device worked. They contacted Hewlett-Packard, which had developed a method for reading eroded cuneiform tablets that involved building up a composite computer image from pictures taken under light from a wide variety of directions, to reveal more of the inscriptions. They enlisted experts in computer-assisted tomography from British firm XTEC, which developed a new machine just for the Antikythera project.

In autumn 2005, the Hewlett-Packard equipment and all 12 tonnes of XTEC's machinery were shipped to the museum. The results have allowed the team to confirm many of Wright's ideas, and extend them. "My main fear initially was that we'd throw all this technology at it and we wouldn't do more than dot the i's and cross the t's," says Freeth. "But we got more out of it than I dared hope."

One major new result came as much from chance as from technology; a key section of a dial found sitting unnoticed in the museum's store room helped reveal that one of the dials was used to predict eclipses. Another big discovery was the identification of a 'pin and slot' mechanism to model the varying speed of the Moon through the sky (see main story).

The inscriptions are also revealing novelties, although deciphering them is hard work: some of them are less than 2 millimetres high, and there are no spaces to show where each word starts and finishes. Agamemnon Tselikas, director of the Centre for History and Palaeography in Athens, spent a concentrated three months trying to decipher the wording, working from late at night into the early hours of the morning: "I needed the silence."

So far Tselikas and his colleague Yanis Bitsakis have more than doubled the number of legible characters on the mechanism, which seem to form a manual that explains how the mechanism was to be used. It takes "imagination and intuition" to decipher the inscriptions, says Tselikas. "We are just starting to penetrate the mentality of the user of this machine."

|

With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. - Steven Weinberg, 1999

|

|

|

|